Policing of Indigenous Bodies by Colonisers: Dialogues on Cultural Memory, Colonial Morality and Contemporary Media

Manufacturing Categories, Embodied Histories

Digital Global South Fellowship • C²DH • University of Luxembourg

2025

Knowledge Before Conquest

"The cultural effects of colonialism have too often been ignored or displaced into the inevitable logic of modernization and world capitalism; but more than this, it has not been sufficiently recognized that colonialism was itself a cultural project of control."

— Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge (1996)

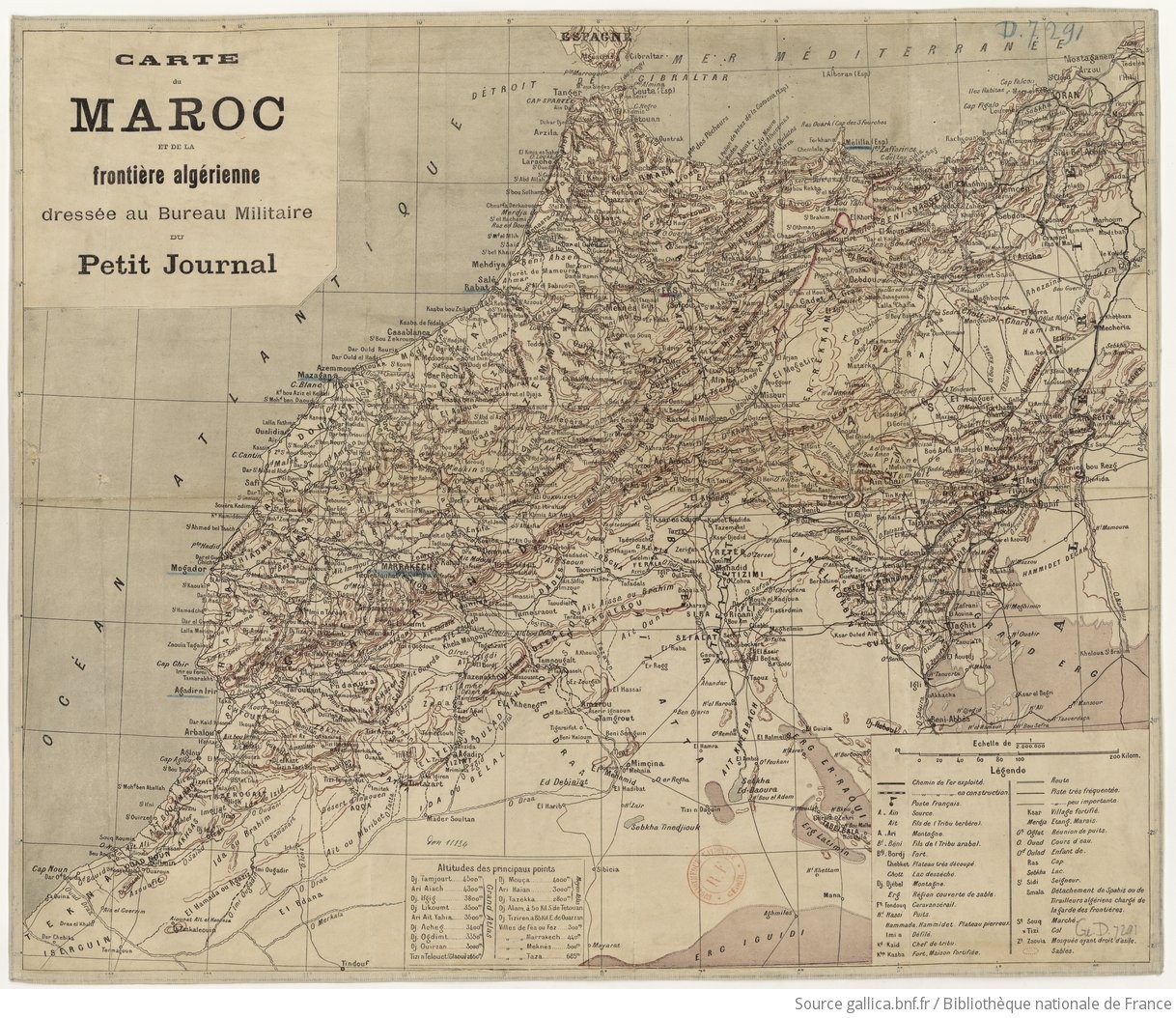

Before the first French soldier set foot in Morocco, before the British East India Company became the British Raj, there were cartographers, surveyors, and ethnographers. Before conquest, colonialism began with classification.

This chapter traces how European powers built large archives of knowledge about the peoples they intended to govern. In Morocco, as in India, the production of colonial knowledge was a deliberate strategy of control, rather than a neutral scientific endeavor.

The Ethnographic State: Morocco

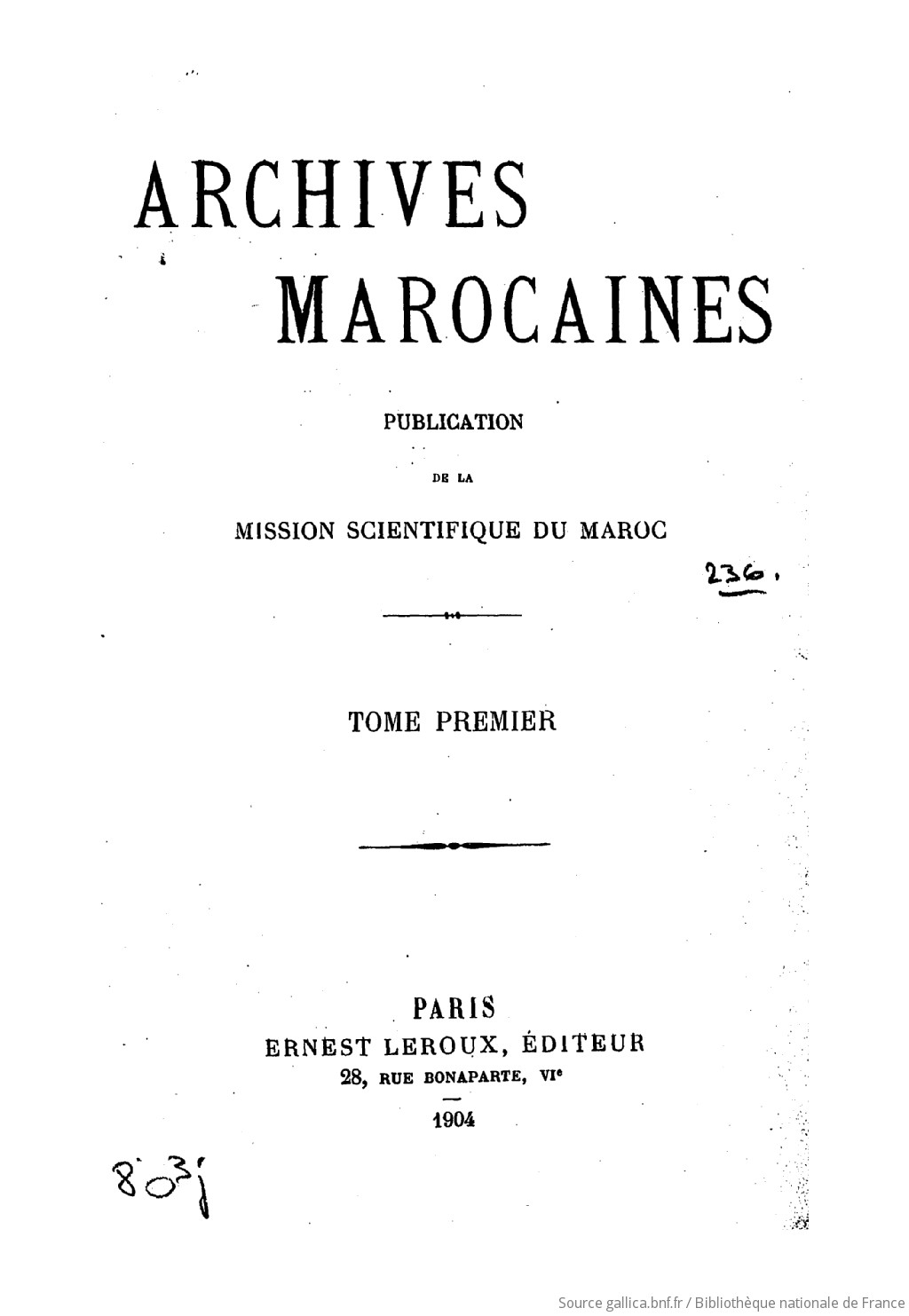

In 1903, nine years before France established its Protectorateالحمايةal-ḤimāyaFrench "protection" of Morocco (1912–1956) — colonial rule disguised as guardianship. over Morocco, the Mission Scientifique du Marocالبعثة العلميةMission ScientifiqueFrench scientific mission (1904–1912) that mapped Morocco's tribes, customs, and territories before conquest. was founded in Tangier. This institution, composed by ethnographers, geographers, geologists, explorers and orientalists, had a single objective: to make Morocco legible to French administrators.

In 1904, the Mission published the journal Archives Marocaines, which provided exhaustive documentation on Moroccan tribes, religious practices, legal customs, and territorial boundaries. In 1912, when the Treaty of Fez formalized French protectorate, the colonial administration had at its disposal exceptional archives on a country it did not yet govern.

"A manifestation of French intellectual power about the Moroccan other, the colonial archive organized knowledge into categories based on then relevant assumptions, which over time could and did change."

— Edmund Burke III, The Ethnographic State: France and the Invention of Moroccan Islam, University of California Press, 2014

Major contributors to the French colonial archive on Morocco: Edmond Doutté (1867–1926), author of En Tribu (1914); Eugène Aubin, author of Le Maroc d'aujourd'hui (1904); and Alfred Le Chatelier, sociologist of Islam and founder of the Mission Scientifique.

Morocco: The Berber Dahir of 1930

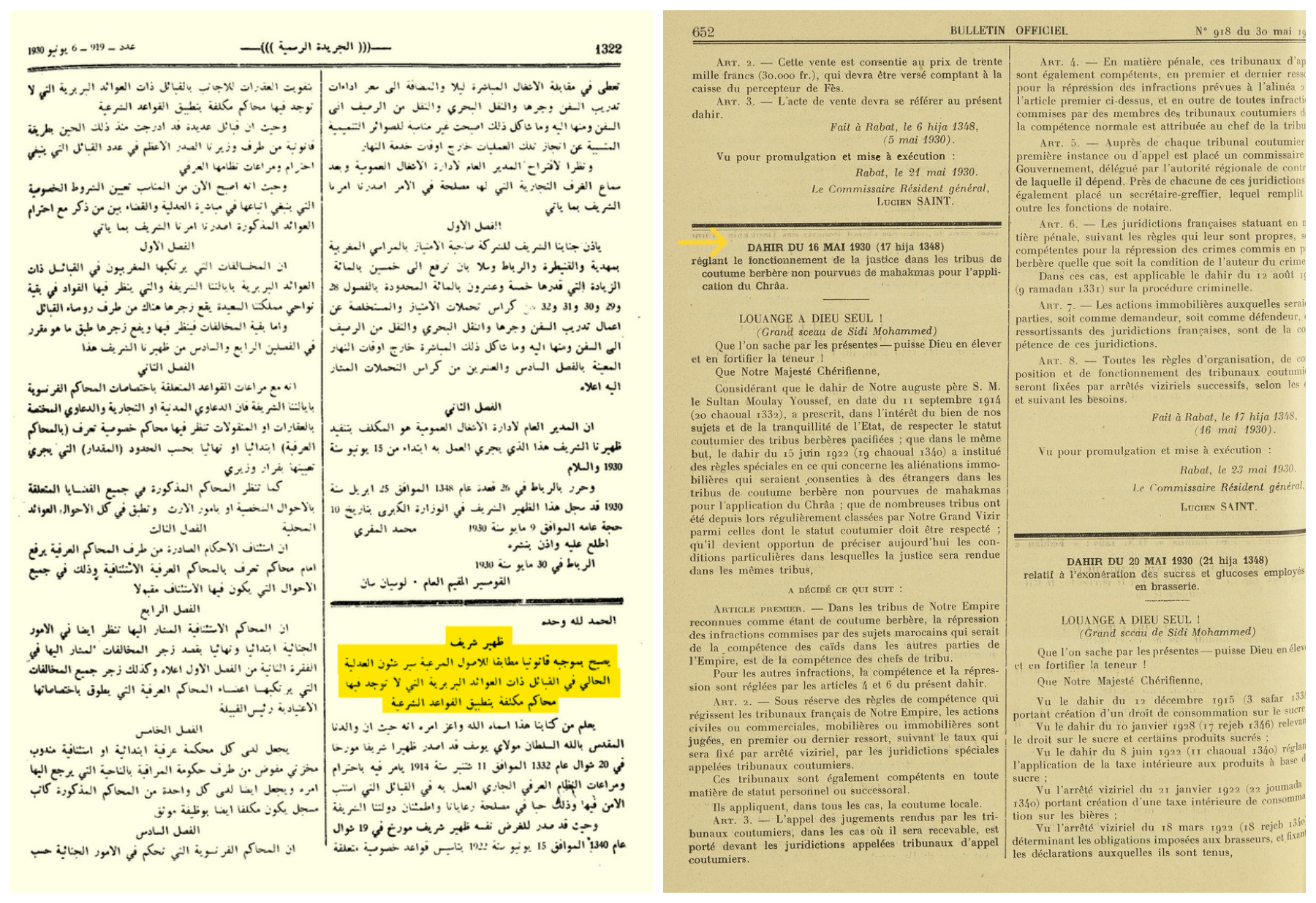

On May 16, 1930, the French Residency in Morocco published a royal decree (a dahirظهيرẒahīrRoyal decree issued by the Moroccan Sultan — under the Protectorate, often drafted by French administrators.) which would trigger the first mass nationalist movement in Moroccan history.

The Berber Dahir (Dahir Berbère) placed Berber-speaking tribes under French customary law and the jurisdiction of French courts, thereby removing them from the jurisdiction of Shariaالشريعةal-SharīʿaIslamic law derived from the Quran and Hadith — the Berber Dahir aimed to sever Berbers from this shared legal tradition. law and the religious authority of the Sultan. On the surface, the decree claimed to respect Berber "traditional customs." In reality, it aimed to separate Berbers from the Arab-Islamic identity that united Morocco.

Source: Internet archive

The Berber Dahir, published in the "Bulletin Officiel du Protectorat de la République Française au Maroc", No. 918, May 23, 1930.

Source: Bibliothèque Diplomatique Numérique

The policy reflected decades of French politique berbèreالسياسة البربريةPolitique Berbère"Berber policy" — French colonial strategy to separate Berbers from Arabs, portraying them as closer to Europeans and less Muslim., according to which Berbers were racially and culturally distinct from Arabs, closer to Europeans, less attached to Islam, and therefore more receptive to French civilization.

"Passant par transitions souvent rapides des prescriptions d'un droit coutumier singulièrement primitif — bien que très vivant et merveilleusement adapté parfois aux circonstances économiques de l'existence — aux règles rigides établies par la législation sacrée du Coran, les Berbères voient ainsi se précipiter, après leur soumission, la ruine des traditions auxquelles ils sont secrètement le plus attachés."

Robert Montagne's Les Berbères et le Makhzen dans le Sud du Maroc (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1930), published the same year as the Dahir, provided ethnographic justification for separate Berber administration, presenting the Arab-Berber distinction as ancient and essential.

— Robert Montagne, Les Berbères et le Makhzen dans le Sud du Maroc, 1930

Education as Division

While the Dahir was the public face of division, the deeper work was done in secret. In an internal memo dated June 25, 1924, Marshal Lyautey stated the purpose of separate Berber schools was to "tame the indigène, and to maintain—discreetly, but as firmly as possible—the linguistic, religious, and social differences that exist between the Arabized bled makhzenبلاد المخزنbilād al-makhzanTerritories under direct control of the Sultan's government. and the Berber mountains, which, while religious, are pagan and ignorant of Arabic."

Source: dafina.net forums (lamgaz, 31 January 2015)

The model school was the Collège Berbère d'Azrou, founded in 1927. French and Berber (in Latin alphabet) were the languages of instruction, while Arabic was banned. By 1950, 250 of Morocco's 350 official caïds were graduates of the Collège d'Azrou..

But this strategy backfired on its authors. In February 1944, the students of Azrou went on strike in solidarity with the nationalist movement, directly rejecting the colonial logic that had led to the creation of their school. After independence, the school was renamed Lycée Tarik ibn Ziyad, after the Amazigh general who led the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula..

The Colonial Construction of "Arab" versus "Berber"

French ethnographers constructed a "Berber Myth" (le mythe berbère), a clear binary distinction "Arab" and "Berber" populations that was part of a moral hierarchy:

THE "BERBER" (Le Mythe Berbère)

- - Indigenous to North Africa, predating Arab "incursion." Linked to a "white race" — European types (Gauls, Germans)

- - Superficially Islamized, retaining "pagan" roots. Non-fanatical. Syncretic Islam (maraboutism, Sufi brotherhoods)

- - Customary law (izerf, qanouns) — judged "in harmony with French code"

- - Democratic, tribal, governed by councils (jama'at). Fiercely independent (bled al-siba)

- - "Eminent qualities": frank, loyal, hardworking, practical, honest, alert

- - Assimilable. Must be "protected" from Arabization and Islamization

THE "ARAB" (Le Gospel Colonial)

- - Invader from Arabia. Origins deemed "fanciful." Race perceived as Semitic

- - Fanatical Muslim. Islam as "negative," "obscurantist." Source of "contagion"

- - Islamic law (sharia)

- - Allied with Makhzan (central authority). Feudal structure, supporting powerful qaids

- - Lazy, slow, cold, dreamy

- - Resistant to progress. Source of "contamination"

This binary concealed the reality. As early as 1901, Edmond Doutté described the distinction between Arabs and Berbers as "vain", pointing out that the communities intermarried, that many spoke both languages (Arabic and Amazigh), and that both groups included nomadic and sedentary populations. The distinction between Bled Makhzenبلاد المخزنBled al-MakhzenLands under central government authority. (lands under central authority) and Bled Sibaبلاد السيبةBled al-Siba"Land of dissidence" — areas outside central control, but not lawless. (lands outside central control) was also distorted, presented as an eternal racial division rather than a changing political relationship. Yet political opportunism won: by 1919, the myth had become an official policy that justified the Berber Dahir a decade later.

Abdeljalil Lahjomri, in his book "Maroc des heures françaises", dismantles the "Berber Myth" element by element, presenting it as a colonial fabrication designed to fracture what was, in reality, a profoundly unified society.

— Abdeljalil Lahjomri, Maroc des heures françaises, 2019

India: Caste as Colonial Category

In India, the British did not invent the caste system, but they transformed it. What had previously been a fluid, regional, and contextual system of social organization became, under colonial rule, a rigid, numbered hierarchy applicable to all of India.

The decennial census, which began in 1871, required colonial administrators to classify every Indian according to caste. This act of numbering had profound consequences:

Fixation of fluid categories: Local jatisசாதிJātiBirth group — occupational/kinship communities, often local and fluid. (occupational/kinship groups) were forced to conform to standardized varnaவர்ணம்VarnaThe four-fold textual classification — a Brahmanical ideal, not lived reality. categories accross India.

Creation of hierarchy: the 1901 census conducted by Herbert Hope Risley classified castes according to their "social precedence," creating official hierarchies where ambiguity had existed.

Mobilization: Once caste became an official category, groups organized to improve their ranking in the census, making caste more politically important than ever.

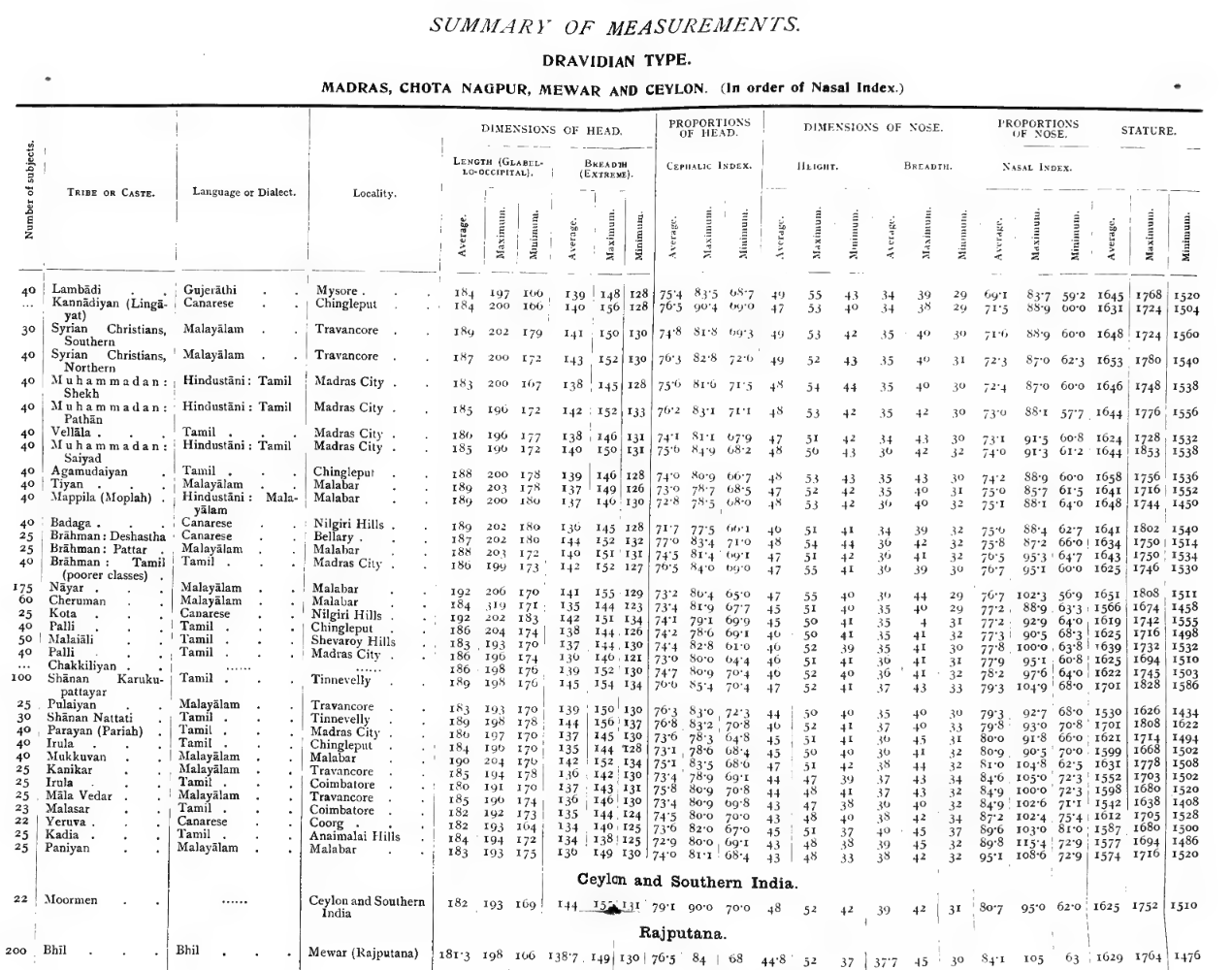

Source: H.H. Risley, The People of India, 1908

Herbert Hope Risley (1851–1911) was the most influential architect of the colonial caste classification system. As Census Commissioner in 1901, he established a system that ranked castes according to the “respect” accorded to them by higher castes, thereby codifying social prejudices as scientific facts. His work also incorporated anthropometric theories, using measurements such as the “nasal index” to assert that caste distinctions reflected racial differences between "Aryan" and “Dravidian” populations.

The "Martial Races" Theory

Beyond the caste system, British administrators developed the theory of martial racesபோர் இனங்கள்Martial RacesBritish theory that some Indian communities (Sikhs, Gurkhas, Pathans) were "naturally" warlike — a political fiction created after 1857. according to which certain Indian communities were naturally warlike and loyal, while others were effeminate and untrustworthy.

After the 1857 Revolt1857 புரட்சிSepoy Mutiny / First War of IndependenceMajor uprising against British rule — called "Mutiny" by the British, "First War of Independence" by Indians., in which Bengali sepoys played a major role, the British restructured the Indian Army to favor Sikhs, Gurkhas, Pathans, and Punjabi Muslims, groups considered "martial", while excluding Bengalis, Marathas, and South Indians. The theory had no scientific basis. It was a political response to the 1857 revolt, designed to recruit from communities deemed loyal and exclude those considered dangerous.

Parallel Strategies, Parallel Consequences

The French in Morocco and the British in India pursued remarkably similar divide-and-rule strategies:

MOROCCO

- — Arab vs. Berber

- — Berbers as "less Muslim"

- — Berber Dahir (1930): separate legal systems

- — Bled Makhzen vs. Bled Siba as eternal divide

INDIA

- — Hindu vs. Muslim

- — "Martial races" as more loyal

- — Separate electorates (1909): separate political systems

- — Caste as unchanging essence

In both cases, colonial administrators took fluid, contextual identities and fixed them into rigid categories. These categories were presented as ancient and natural, obscuring their recent political origins. They had real consequences (legal, economic, social) that made them self-fulfilling.

Burke III,Edmund. The Ethnographic State: France and the Invention of Moroccan Islam. University of California Press, 2014.

Burke III,Edmund. The Creation of the Moroccan Colonial Archive, 1880–1930. Routledge, 2007.

Montagne, Robert. Les Berbères et le Makhzen. Félix Alcan, 1930.

Tyrey, Adrienne. Divide and School: Berber Education in Morocco under the French Protectorate. Michigan State University, 2018.

Laroui, Abdallah. The History of the Maghrib. Princeton UP, 1977.

Lahjomri, Abdeljalil. Maroc des heures françaises. Marsam, 2019.

El Qadéry, Mustapha. Les Berbères entre le mythe colonial et la négation nationale. Le cas du Maroc. 1998.

Tilmatine, Mohand.French and Spanish colonial policy in North Africa: revisiting the Kabyle and Berber myth. De Gruyter, 2016.

Wyrtzen, Jonathan. Colonial State-Building and the Negotiation of Arab and Berber Identity in Protectorate Morocco.Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Dirks, Nicholas B. Castes of Mind. Princeton UP, 2001.

Risley, H.H. The People of India. Thacker, Spink & Co., 1908.

Bayly, Susan. Caste, Society and Politics in India. Cambridge UP, 1999.

Resistance & Bodies

"The colonized is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country's cultural standards."

— Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

Colonial rule classified territories and populations. It also classified bodies. In Morocco and India, European administrators encountered communities that threatened colonial control, as well as female artists whose art blended the sacred and the sensual. Both became targets.

This chapter traces two forms of colonial intervention and their unintended consequences. First, strategies of division that often had the opposite effect to that intended: by attempting to separate communities from their common identities, the colonial powers involuntarily created the conditions for mass mobilization. Second, colonial moral campaigns targeted bodies, particularly those of women, that defied European categories of respectability. In Morocco, the Shikhate who sang songs of resistance were imprisoned, tortured, and silenced. In India, the Devadasis who danced in devotion were abolished by law.

Morocco: The Ya Latif Protests (1930)

The Berber Dahir sparked the first mass nationalist movement in Moroccan history. Within weeks, demonstrations broke out across the country, with the collective recitation of the Latif Prayer in mosques. Ya Latifيا لطيفYā Laṭīf"O Gentle One" — one of the 99 names of God in Islam, invoked in the 1930 protests., "O Gentle One," is traditionally invoked in times of calamity.

يا لطيف، نسألك اللطف فيما جرت به المقادير، لا تفرق بيننا وبين إخواننا البرابر

"O Gentle One, we ask Your gentleness in what fate has decreed.

Do not separate us from our Berber brothers."

— The Latif Prayer, recited in Moroccan mosques, 1930

By representing the resistance as a religious duty, Moroccan nationalists united Arab and Berber Muslims, made repression difficult, and mobilized women and uneducated people through mosque networks. In 1934, France was forced to revoke the most controversial provisions of the Dahir.

Key Figures in Moroccan Nationalism

Allal al-Fassiعلال الفاسيʿAllāl al-Fāsī(1910–1974) Founder of Moroccan nationalism, later leader of the Istiqlal (Independence) Party. (1910–1974): One of the founders of Moroccan nationalism, later leader of the Istiqlalالاستقلالal-Istiqlāl"Independence" — Moroccan nationalist party founded in 1944, emerged from the 1930 protests. (Independence) Party. Al-Fassi was arrested multiple times for his role in organizing resistance.

Mohammed Hassan al-Ouazzani (1910–1978): Journalist and nationalist leader who helped publicize the Dahir crisis internationally.

Ahmed Balafrej (1908–1990): Co-founder of the nationalist movement who helped organize the Paris-based protests.

India: The Devadasis

The word DevadasiதேவதாசிTēvatāci"Servant of god" — women dedicated to temples, custodians of classical dance. means "servant of god." For centuries, Devadasis were women ritually consecrated to Hindu temples, where they performed sacred dances, maintained the temple grounds, and served as guardians of the classical arts.

Devadasis occupied a complex social position. Ritually married to the deity, they were nityasumangaliநித்யசுமங்கலிNityasumaṅgalī"Ever-auspicious woman" — a Devadasi could never be widowed, as her divine husband was immortal., "ever-auspicious" women who could never be widowed. Their dance, the Sadhirசதிர்SadirOriginal temple dance tradition, later renamed Bharatanatyam., incorporated Shringaraசிருங்காரம்ŚṛṅgāraThe erotic sentiment — in temple context, devotion expressed through divine love., erotic feeling, as an essential aesthetic component. In Hindu temple theology, erotic devotion to the deity was sacred.

The Anti-Nautch Movement

British missionaries and colonial administrators viewed Devadasi traditions through the prism of Victorian sexual morality. What they saw scandalized them: women dancing in temples in front of men, women outside of marriage, women whose art celebrated eroticism.

The Anti-Nautch Movement emerged in the 1890s, led by an alliance of British missionaries and Indian social reformers. Nautchநாட்ச்NautchFrom Hindi "nāch" (dance) — term of disapproval applied to Indian dance traditions by the Anti-Nautch movement. (from Hindi nāch, meaning dance) became a pejorative term applied to all Indian dance traditions.

"Whatever may, in the very beginning, have been the conception of thus devoting girls to gods and temple service, it is now, and has been for centuries, a most debasing custom. They are invariably courtesans sanctioned by religion and society. [...] These girls are the common property of the priests. Wicked men visit the temple, ostensibly to worship, but in reality to see these women. And what shall we say of the simple-minded, but well-to-do pilgrim, should he fall under their power ? He will probably return to his home a ruined man. That a temple, intended as a place of worship, and attended by hundreds of simplehearted men and women, should be so polluted, and that in the name of religion, is almost beyond belief; and that Indian boys should grow up to manhood, accustomed to see immorality shielded in these temples with a divine cloak, makes our hearts grow sick and faint."

— Marcus B. Fuller, The wrongs of Indian womanhood, 1900.

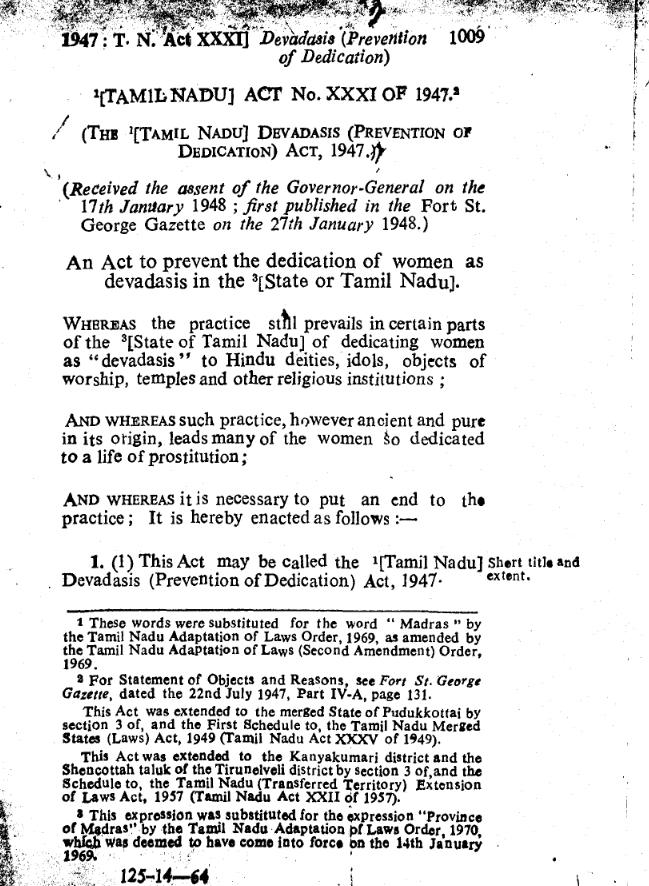

This movement portrayed Devadasis as prostitutes, thereby erasing the distinction between sacred ritual and sex work. Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi (1886–1968), the first woman legislator in British India, led the campaign to abolish this practice. Her Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act passed in 1947, criminalized temple dedication and effectively abolished the institution.

Source: India Code - Digital Repository of Laws

Morocco: The Shikhate

Shikhateالشيخاتal-ShīkhātProfessional female singer-dancers of Morocco, practitioners of Aïta poetry. Custodians of oral tradition, stigmatized under colonial and reformist morality. (singular: Shikha) are Moroccan poetesses, singers, and dancers who practice Aïtaالعيطةal-ʿAyṭa"The cry" — Moroccan oral poetry tradition performed at festivals. Themes include love, loss, social commentary, and resistance. or “cry,” a genre of oral poetry.

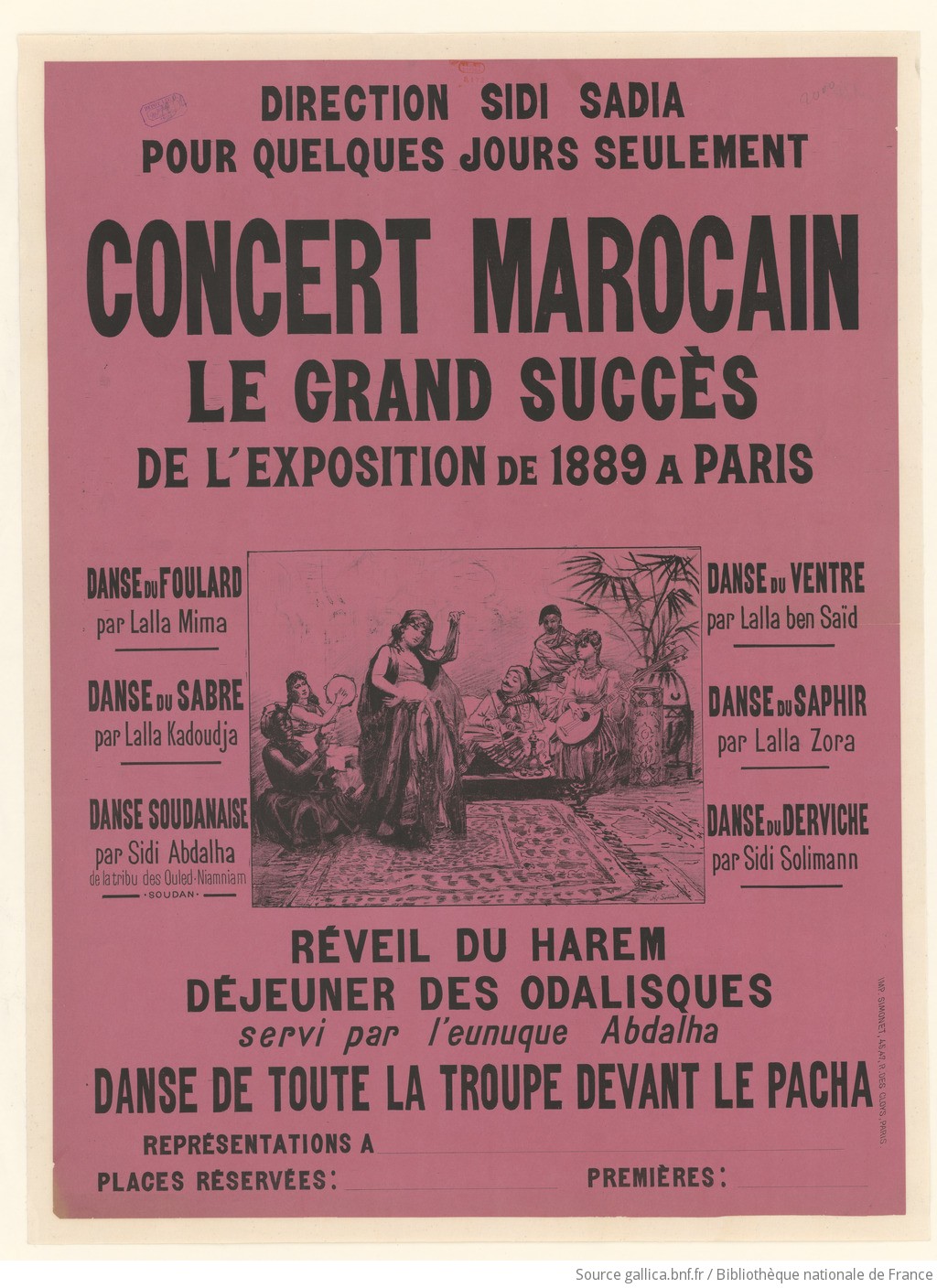

Aïta originated in rural folk poetry performed at festivals, weddings, and community gatherings. Its themes include love, loss, social commentary, and resistance. During the colonial period, the Shikhate performed songs encoding anti-colonialist sentiments and transmitted important news throughout the countryside in the songs they passed on with their troupes from village to village. This made them dangerous to the colonial project.

The French recognized the mobilizing power of the Aïta, so their reaction was to strategically degrade the Shikhate.

"During colonialism, the French wanted to get rid of the ʿaita because it could mobilize people, carry the nationalist message everywhere. It was the French that during the Protectorate created brothels where soldiers could be entertained by the shikhat. That is how the poetic language of the ʿaita changed from a language of the people to an erotic language associated with alcohol and prostitution."

— Mohammed Bouhmid, scholar of Aïta tradition, cited by Alessandra Ciucci in “De-orientalizing the ʿAita and Re-orienting the Shikhat”, 2010.

This was indeed a policy, not passive stigmatization: containing tradition by corrupting its context, transforming poets into entertainers for soldiers, severing the link between artists and their community. Pasha Thami al-Glaouiالتهامي الكلاويal-Thāmī al-Glāwī(1879–1956) Pasha of Marrakech and French collaborator. Helped orchestrate Mohammed V's exile in 1953. did this explicitly by administratively grouping shikhate and prostitutes in the same neighborhood (ماخور عرصة الحوتة) purposefully blurring the lines between the two professions.

Voices of Resistance: The Shikhate Who Fought Back

Yet the Shikhate resisted and their names deserve to be remembered:

Shikha Kharbouaa (خربوعة), born Zahra al-Hamdi in 1929, was a master of Aïta Zaïriya. In 1953, she improvised a song denouncing Mohammed V's exile to Madagascar. She was arrested and imprisoned in five different prisons: Rommani, Oued Zem, Khouribga, Ben Ahmed, and finally a full year in Casablanca's Ghbila prison. She was released only after the King's return, in a general amnesty for "prisoners of conscience." She died in poverty in 2017, having spent her final years in charity queues.

— Al Akhbar, "الشيخات بين الأمس واليوم"

Hajja al-Hamdawiya (الحمداوية) was repeatedly arrested for songs inciting resistance. After every performance, she was summoned for interrogation about the meanings behind her lyrics. Her song "الشيباني" (The Old Man), with its line "آش جاب لينا حتى بليتينا" ("What brought him to us until he ruined us"), was interpreted as mocking Ben Arafa, the puppet sultan France installed after exiling Mohammed V. She was imprisoned and tortured for these words.

— Al Akhbar, "الشيخات بين الأمس واليوم"

Shikha Kharboucha (خربوشة), also called Hadda "Lkerda," composed poetry inciting her tribe, Oulad Zaid, to rebel against Caid Aissa Ben Omar. She was captured through a trap and imprisoned in his fortress. From her cell, she composed: "الليلة العذاب أبابا ونقاسي.. الدنيا تفوت أبابا نقاسي.. آخرها موت" ("Tonight the torture, father, I suffer... Life passes, father, I suffer... Its end is death"). According to oral histories, her tongue was cut out before she was killed.

— Al Akhbar, citing researcher Mustafa Lotfi

Al-Niria (النيرية), born Mbaraka bint Hammu al-Bahishiya, composed "الشجعان" (The Heroes), a battle anthem for resistance fighters in Tadla and Beni Mellal. She rode horseback carrying henna water: any fighter who retreated was splashed, marking him as a coward before his tribe. Men preferred death in battle to returning home stained with her henna. The French prosecuted her for inciting resistance, yet she never received official recognition as a member of the resistance.

— Al Akhbar, citing researcher Mohammed Boukhar

The Colonial Gaze

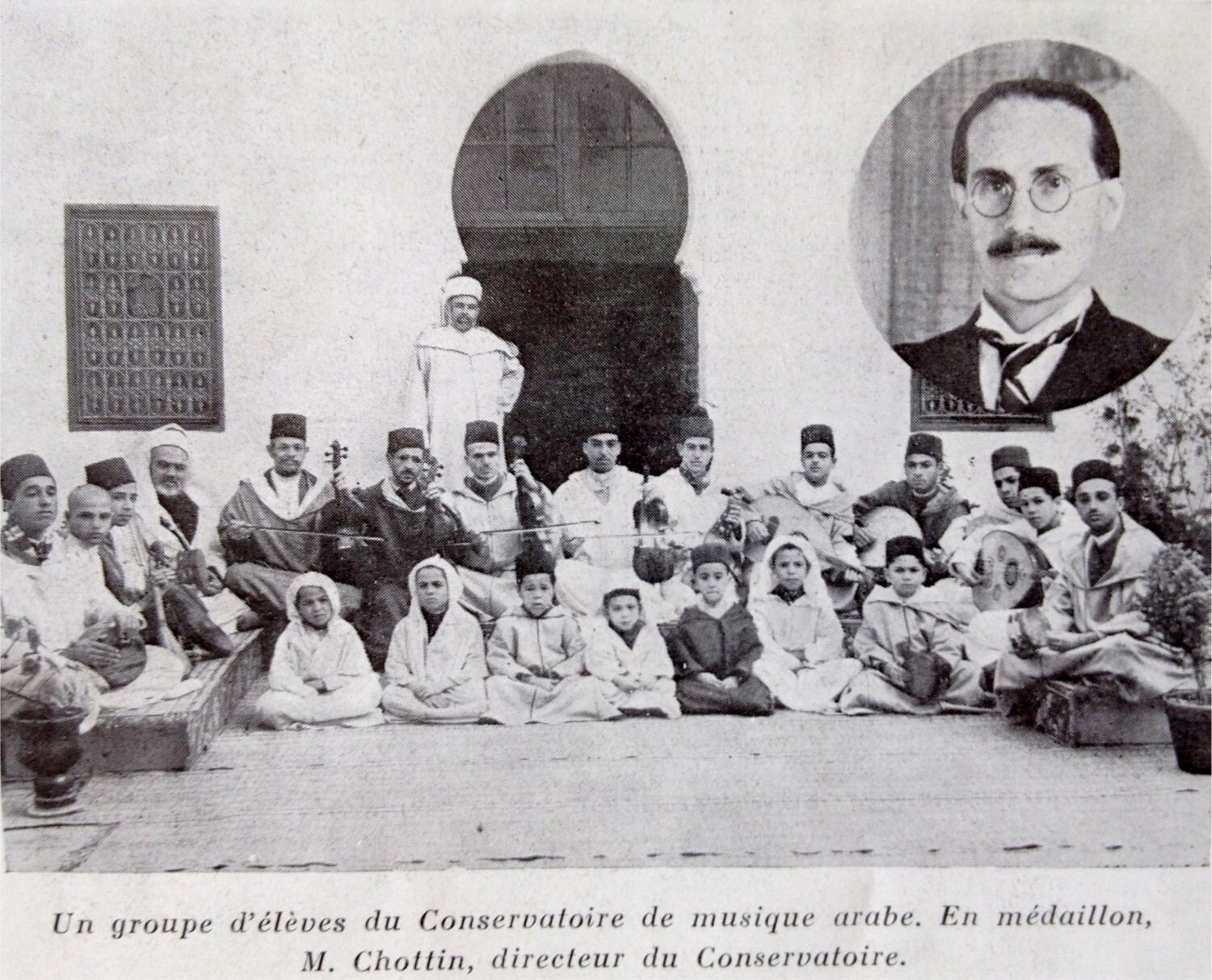

French musicologist Alexis Chottin exemplifies the colonial attitude toward Shikhate's performances in 1928:

"Nous allons connaître le Maroc libertin et jouisseur. Ce 'visage' est agréable à regarder, mais que de fard sur les joues, que de khôl sous les yeux… Et j'ai bien peur, hélas! que là-dessous il n'y ait qu'une pauvre et menue figure, pâlotte et fripée de viveur… Ce rire et cette joie fusent et éclatent dans le rythme, rythme étourdissant, rythme enchanteur qui endort les soucis et les peines; rythme-vampire dont les ailes s'agitent pour anesthésier la douleur causée par sa morsure fatale."

— Alexis Chottin, "Les visages" de la musique marocaine, 1928

This passage illustrates the dual colonial dilemma: a mixture of fascination and condemnation. Shikhate are described as “libertine and pleasure-seeking.” Makeup, kohl, and jewelry are considered to conceal “a poor and petite figure.” The rhythm is both “enchanting” and “vampiric.” Chottin cannot look away, but he expresses it as a moral warning. This same musicologist would later classify Aïta as a rather vulgar art and Andalusian music as “refined,” thus colonial hierarchy took the form of scholarly language.

Parallel Patterns

Despite vast differences in religious context, the Devadasi and Shikhate faced strikingly similar fates:

Devadasi (INDIA)

- • Temple dancers, "servants of god"

- • Ritually married to deity

- • Economically independent

- • Custodians of Sadhir dance

- • Targeted by Anti-Nautch movement

- • Legally abolished (1947)

- • Term became slur: "Thevadiya"

SHIKHATE (MOROCCO)

- • Festival performers, poets of Aïta

- • Outside conventional marriage

- • Economically independent

- • Custodians of oral poetry

- • Targeted by colonial/reformist morality

- • Imprisoned, tortured, killed

- • Term became insult in Darija

The Sacred and the Sensual

These two traditions challenge a distinction that colonial morality took for granted: the separation between the sacred and the sensual. In Hindu temple theology, erotic devotion (bhakti infused with shringara) was a legitimate path to the divine. The poet-saint Andalஆண்டாள்Āṇṭāḷ8th-century Tamil poet-saint who wrote passionate love poetry addressed to Vishnu. Her works are still recited in temples today. (8th century) wrote passionate love poems to Vishnu, which are still recited today in temples. In the Moroccan Sufi tradition, ecstatic practices, particularly music and dance, were pathways to divine experience.

Colonial morality had difficulty accepting these practices. The dancing body was either sacred OR sensual, not both at the same time. By imposing this binary vision, colonialism completely altered the relationship of local populations to art, spirituality, and the body.

Chottin, Alexis. "Les visages" de la musique marocaine. Imprimerie Nouvelle, 1928.

Ciucci, Alessandra. De-orientalizing the ʿAita and Re-orienting the Shikhat. Cambridge Scholars Press, 2010.

Pasler, Jann. Co-producing knowledge and Morocco's musical heritage: a relational paradigm for colonial scholarship. Routledge, 2022.

Basri, Hassan. الشيخات بين الأمس واليوم عندما كانت الشيخة رمزا لمعارضة. Al Akhbar, 25 April 2022.

Baji, Oussama. الشيخات في المغرب: ماض منسي وألقاب مهينة وواقع مجروح Marayana, 18 November 2022.

Soneji, Davesh. Unfinished Gestures. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Kersenboom, Saskia. Nityasumangali. Motilal Banarsidass, 1987. Fuller,Marcus B. The wrongs of Indian womanhood.Revell, New York, 1900.

Afterlives

"It's essentially an upper-caste woman appropriating the arts and culture of lower-caste women and taking ownership of the dance form."

— Abirami

Colonialism transformed what it could not completely destroy. Traditional artistic practices were subjected to “sanitization”: the removal of elements deemed immoral by colonial and nationalist elites. Artists themselves were erased from the traditions they had created and preserved.

This chapter traces what happened next: how indigenous arts were remade for respectable consumption, how colonial categories survived colonial rule, and how the wounds inflicted on names, “Thevadiya” in Tamil and “Shikha” in Darija, continue to hurt in the digital age.

From Sadhir to Bharatanatyam

In the 1930s, as the Anti-Nautch movement stigmatized Devadasi traditions, a counter-movement emerged that sought to "save" Indian dance by separating it from the women who performed it.

Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904–1986), a Brahmin woman, founded Kalakshetraகலாக்ஷேத்ராKalākṣetra"Temple of art" — institution founded in 1936 that became the center of "classical" Bharatanatyam, teaching upper-caste women the dance forms learned from Devadasi masters. in 1936, transforming temple dance into a concert performance. The new name, Bharatanatyamபரதநாட்டியம்Bharatanāṭyam"Classical" dance created from Sadhir in the 1930s–40s. The Sanskrit name (Bharata + Natyam) erased Tamil Devadasi origins, claiming instead a pan-Indian classical lineage., claimed a Sanskrit lineage: Bharata (the sage who authored the Natyashastra) + Natyam (dance). The Tamil temple context was erased.

SADHIR (Devadasi)

- • Performed in temples

- • Ritual and devotional function

- • Hereditary practice

- • Shringara (erotic sentiment) central

- • Addressed to the deity

BHARATANATYAM (REVIVAL)

- • Performed on proscenium stages

- • Aesthetic and cultural function

- • Taught to upper-caste women

- • Shringara minimized or spiritualized

- • Addressed to audience

Upper-caste women learned from Devadasi masters, then presented the dance as a recovered "classical" tradition belonging to Hindu civilization broadly. The teachers were acknowledged in private; in public, they disappeared. T. Balasaraswati (1918–1984), a Devadasi-lineage dancer, maintained the centrality of shringara and resisted the spiritualization of erotic content. But it was Rukmini Devi's sanitized version that became dominant.

Devadasi Voices & Heritage

Morocco: The Hierarchy of Sound

Alexis Chottin's colonial taxonomy, which classified Andalusian music as “classical” and Aïta as “folk,” was adopted by the postcolonial state. After independence (1956), conservatories were created to preserve al-Ālaالآلةal-ĀlaAndalusian classical music, associated with Muslim refugees from Spain after 1492. Elevated as Morocco's "refined" tradition by colonial and postcolonial authorities., the Andalusian tradition. These conservatories still rely on Chottin's work for their teaching today.

Meanwhile, Aïta remained at the bottom of the hierarchy: excluded from conservatory programs and underdocumented while "refined" forms were the focus of attention. The Shikhate who preserved this tradition continued to face social stigma.

"Aujourd’hui, les jeunes ont rarement envie de jouer l’Aïta à cause de sa mauvaise réputation et de la précarité financière découlant de sa pratique. Ils s’orientent plutôt vers d’autres formes de musiques, plus pop et plus « rentables ». Les Chikhates, même si certaines sont adulées, font également l’objet de beaucoup de mépris. La réputation parfois sulfureuse qui reste attachée au rôle de la Chikha ne rend pas service à la perpétuation de cette musique. Souvent les enfants refusent de voir leurs mères chanter l’Aïta, ce qui peut être assez préoccupant."

"Today, young people rarely want to perform Aïta because of its bad reputation and the financial insecurity that comes with it. They tend to gravitate toward other forms of music that are more pop-oriented and more “profitable.” Chikhates, even if some are adored, are also the subject of much contempt. The sometimes scandalous reputation that remains attached to the role of the Chikha does not help to perpetuate this music. Children often refuse to see their mothers sing Aïta, which can be quite worrying."— Brahim el Mazned, in an interview with the journal "Hommes & Migration".

Source: François Bensignor, “Aïta, une anthologie”, Hommes & migrations, 2018.

The Wounded Name

Hassan Najmi, poet and scholar of Aïta, borrows Abdelkebir Khatibi's phrase to describe the shikhate's condition: الاسم المغربي الجريحالاسم المغربي الجريحal-Ism al-Maghribī al-Jarīḥ"The Wounded Moroccan Name" — Hassan Najmi's phrase (borrowing from Khatibi) describing how shikhate were given degrading nicknames by those in power, names that became their identity., "the wounded Moroccan name."

The shikhate were given degrading nicknames by those in power: caïds, sheikhs, notables. Names that mocked their physical disabilities, names intended to humiliate them. These names stuck to them, and often became the only names by which these artists were known, even on recordings.

"من يسمي الشيخة؟ أحيانا، يسميها القايد أو الشيخ أو الأعيان وأصحاب المال والنفوذ، لتصبح التسمية متداولة يطلقها من يتمتع بسلطة مادية أو قهرية أو اجتماعية."

"Who names the Shikha? Sometimes the caid, the sheikh, or the notables with money and influence. The name becomes common, given by those with material, coercive, or social power."

— Hassan Najmi, cited in Marayana, 2024

The same wound exists in Tamil. “Devadasi,” servant of God, has become “Thevadiya,” one of the most common insults in that language. Most speakers are unaware of its etymology and may not realize that they are perpetuating colonial moral judgments every time they use it.

Digital Echoes

Colonial categories persist and in the digital age, they proliferate. Slurs derived from colonial-era stigmatization spread across platforms, amplified by algorithms designed to maximize engagement.

TAMIL

தேவதாசி

Devadasi — "Servant of God"

↓

Colonial stigmatization

Anti-Nautch movement (1890s)

Abolition Act (1947)

↓

தேவடியா

ThevadiyaதேவடியாTēvaṭiyāOne of the most common Tamil slurs, derived from "Devadasi." Most speakers are unaware they perpetuate colonial moral judgments. — common slur

MOROCCAN ARABIC

شيخة

Shikha, in classical arabic: "Woman of knowledge"

↓

Colonial + reformist stigmatization

Glaoui's deliberate conflation

20th century marginalization

↓

شيخة

Shikha — insult in Darija

Platforms profit from engagement and content that provokes shame drives engagement. Colonial categories, with their capacity to cause harm, are profitable even if they harm users. Content moderation systems, primarily trained in English, do not detect insults in Tamil, Darija, and other languages. The algorithm cannot read history.

Reclaiming Space

However, these same platforms allow counter-narratives to be heard. Academics share accurate historical accounts. Diaspora communities connect despite the distance. Musicians celebrate traditions that were once stigmatized.

Reappropriationالاستردادமீட்புThe work of recovering traditions, histories, and dignity from colonial distortion. Not returning to a pure past, but building new futures. is not a return to a pure pastbut rather the work of building new futures from wounded histories. It means knowing the etymology of the insult and refusing to give it power. It means naming the shikhate who resisted, the Devadasis who preserved sacred art, the women whose names were stolen and replaced with wounds.

It means calling them by their real names.

Soneji, Davesh. Unfinished Gestures. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Meduri, Avanthi. "Bharatha Natyam—What Are You?" Asian Theatre Journal, 1988.

Aydoun, Ahmed. Musiques du Maroc. Eddif, 1992.

Najmi, Hassan. غناء العيطة: الشعر الشفوي والموسيقى التقليدية في المغرب. 2007.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. 1952.

Sambasivan, N., et al. "Gender and Digital Abuse in South Asia." CHI, 2019.

The Body is a Festival

"El cuerpo dice: Yo soy una fiesta."

— Eduardo Galeano

This exhibition has traced the history of a shame that was manufactured, imposed and inherited. But shame is not the end of the story.

In Morocco and India, artists, academics, and communities are reclaiming the traditions that colonialism sought to erase. The Shikhate continue to perform. The dancers continue to move. The body, despite everything, remains a place of joy.

This epilogue is not a conclusion, but an opening towards a future where colonial categories no longer define what is sacred, what is art, or what deserves our interest.

Reappropriation

Morocco: The Aïta Lives

The tradition of Aïta has never disappeared. Despite marginalization and stigmatization, Shikhate continue to perform at festivals and celebrations throughout Morocco. Today, a new generation of scholars and artists is working to document, preserve, and celebrate this tradition.

Stigmatization has not disappeared, but it is being challenged. Women who practice Aïta today do so in a context where their art is increasingly recognized as heritage.

India: Dancing Forward

The descendants of Devadasi communities continue to navigate a complex heritage. Some have taken up dancing, perpetuating traditions that their grandmothers were not allowed to practice. Others have become scholars, documenting stories that were nearly erased.

Contemporary Bharatanatyam dancers are increasingly recognizing the Devadasi origins of their art. Some seek out surviving practitioners from hereditary communities, learning a repertoire that the colonial morality had deemed unacceptable. The dance scholar Nrithya Pillai, herself from a Devadasi heritage, performs and teaches in a way that honors her community's contributions rather than erasing them.

The Work of Memory

This exhibition is itself an act of memory-work. By placing Moroccan and Indian histories side by side, we bring to light patterns that would otherwise remain invisible. By denouncing colonial violence, we refuse to let it pass as natural or inevitable.

But the work of memory is never complete. The archives remain fragmentary and voices continue to be missing. The women at the heart of these stories, the Devadasis who danced, the shikhate who sang, left few written accounts of their own lives. We try to reconstruct their lives from the archives of those who sought to reform, abolish, or classify them.

This exhibition pays tribute to their presence while acknowledging its limitations. We cannot speak on their behalf, we can only do our best to ensure that their stories are not forgotten.

What We Owe

What do we owe to histories of silence and erasure?

Recognition: The first step is to name what happened. Colonial categories were not natural: traditions were suppressed, transformed, and stigmatized by deliberate policy.

Restitution: Archives held in former colonial empires should be accessible to the communities whose history they contain. Cultural heritage should be returned.

Transformation: Insults that circulate in everyday language carry colonial violence. Every time we use “Thevadiya” or “Shikha” as an insult, we perpetuate that violence. Language can change and categories can be rejected.

Celebration: The traditions that colonialism tried to destroy deserve to be celebrated, not as museum pieces, but as living arts. The Shikhate deserve to be recognized as artists preserving Morocco's cultural heritage. The legacy of the Devadasi deserves to be honored, not shamed.

About This Exhibition

Policing Native Bodies is the result of a collaboration between two scholars working on colonial history. We came to this project from different backgrounds, different languages, different colonial contexts. We discovered parallels: the same logic of classification, the same targeting of female artists, the same transformation of honor into shame.

By bringing these stories together, we hope to reveal the structures that connect them and imagine futures beyond colonial categories.

Digital Global South Fellowship 2025

Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH)

University of Luxembourg

The Researchers Behind This Archive

Ferdaous Affan

Tangier, Morocco → University of Luxembourg

"This work of deconstruction, of trying to be aware of this internalized hatred towards your own identity and culture—it is such huge work one has to do on oneself."

PhD Researcher, C²DH

Computational analysis of colonial propaganda using LLMs

LinkedIn Profile

Abirami Raveendranath

Tamil Nadu, India

"There was a period in my life where I so desperately wanted English to be my mother tongue. That is so sad. Tamil is such a beautiful language."

Digital Global South Fellow 2025

Sociologist, Literary Scholar

LinkedIn Profile