Policing of Indigenous Bodies by Colonisers: Dialogues on Cultural Memory, Colonial Morality and Contemporary Media

Manufacturing Categories, Inheriting Shame

Digital Global South Fellowship • C²DH • University of Luxembourg

2025

Knowledge Before Conquest

"The cultural effects of colonialism have too often been ignored or displaced into the inevitable logic of modernization and world capitalism; but more than this, it has not been sufficiently recognized that colonialism was itself a cultural project of control."

— Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge (1996)

Before the first French soldier crossed into Morocco, before the British East India Company became the British Raj, there were the mapmakers, the surveyors, the ethnographers. Before conquest, colonialism began with classification.

This chapter traces how European powers built vast archives of knowledge about the peoples they intended to rule. In both Morocco and India, colonial knowledge production was a deliberate strategy of control, rather than a neutral scientific endeavor.

The Ethnographic State: Morocco

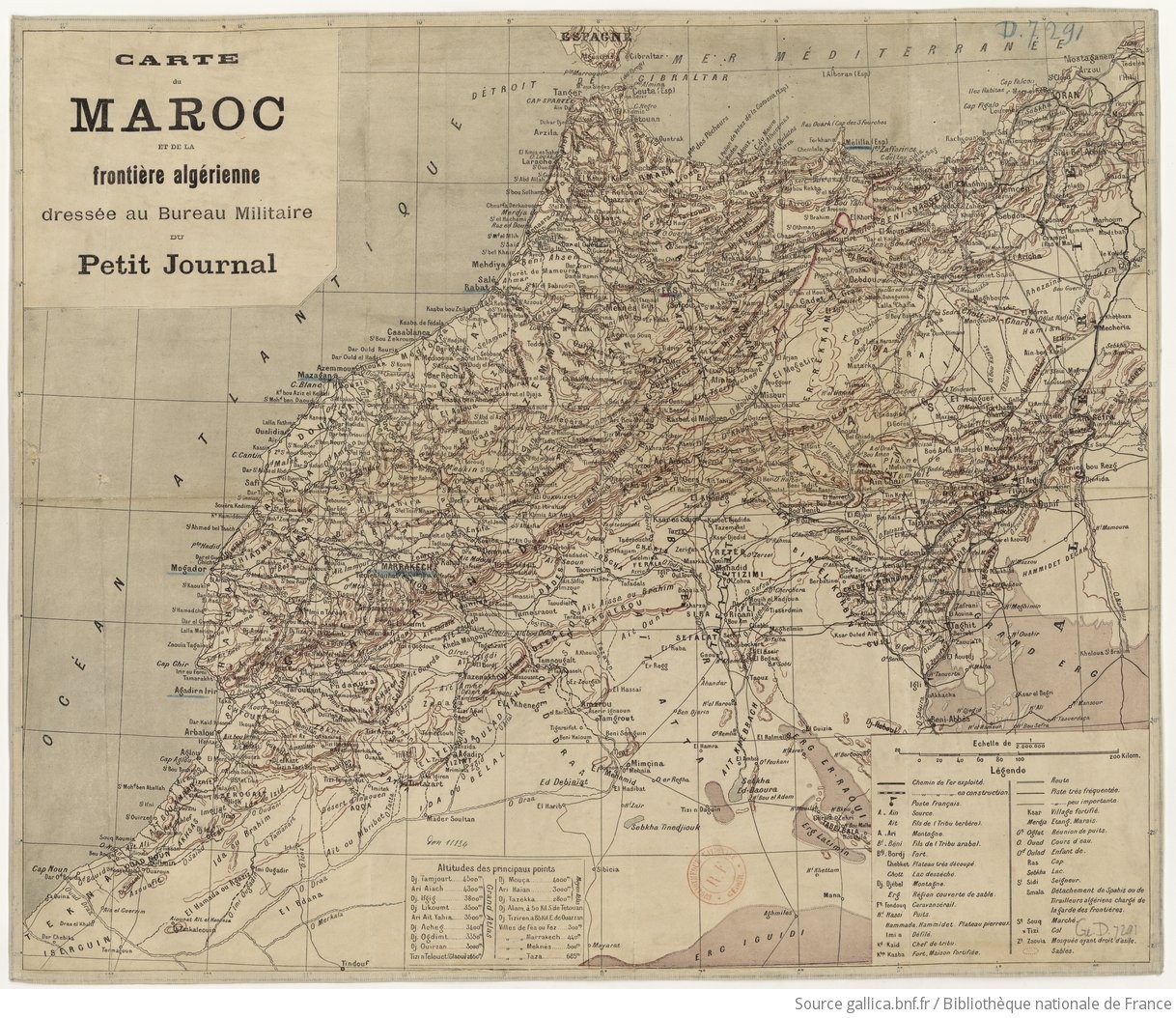

In 1903, nine years before France would establish its Protectorateالحمايةal-ḤimāyaFrench "protection" of Morocco (1912–1956) — colonial rule disguised as guardianship. over Morocco, the Mission Scientifique du Marocالبعثة العلميةMission ScientifiqueFrench scientific mission (1904–1912) that mapped Morocco's tribes, customs, and territories before conquest. was founded in Tangier. This institution, staffed by ethnographers, geographers, geologists, explorers and orientalists, had one purpose: to make Morocco legible to French administrators.

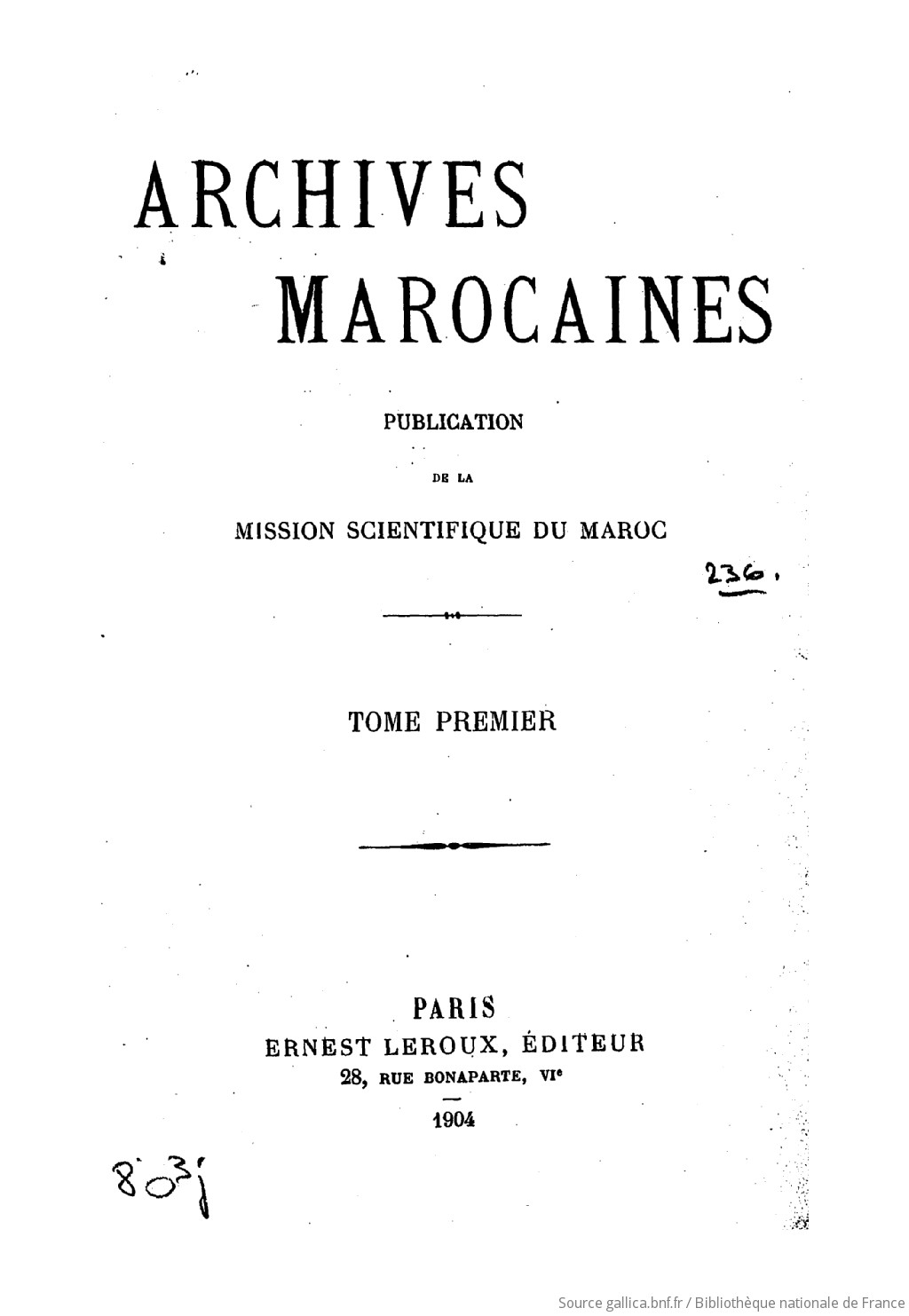

The Mission published in 1904 the journal Archives Marocaines, which systematically documented Moroccan tribes, religious practices, legal customs, and territorial boundaries. By 1912, when the Treaty of Fez formalized French control, the colonial administration possessed an extraordinary archive of information about a country it did not yet rule.

"A manifestation of French intellectual power about the Moroccan other, the colonial archive organized knowledge into categories based on then relevant assumptions, which over time could and did change."

— Edmund Burke III, The Ethnographic State: France and the Invention of Moroccan Islam, University of California Press, 2014

Major contributors to the French colonial archive on Morocco: Edmond Doutté (1867–1926), author of En Tribu (1914); Eugène Aubin, author of Le Maroc d'aujourd'hui (1904); and Alfred Le Chatelier, sociologist of Islam and founder of the Mission Scientifique.

The Information Order: India

The British approach to India established the template that France would later adapt for Morocco. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the East India Company commissioned massive surveys to document the subcontinent.

Colin Mackenzie (1754–1821), a Scottish engineer, conducted one of the most ambitious early surveys, collecting thousands of manuscripts, inscriptions, and maps across South India. His collection, now held at the British Library, represents one of the earliest systematic attempts to archive Indian knowledge for colonial use.

Francis Buchanan conducted surveys of Bengal, Bihar, and other regions between 1807–1814, documenting everything from agriculture to social structures. The Imperial Gazetteer of India, compiled under William Wilson Hunter beginning in 1869, represented the culmination of this knowledge project—a comprehensive encyclopedia spanning geography, ethnography, and administration.

The Census as Colonial Technology

Perhaps no colonial technology shaped indigenous society more profoundly than the census. In India, the decennial census beginning in 1871 did not merely count populations—it classified them.

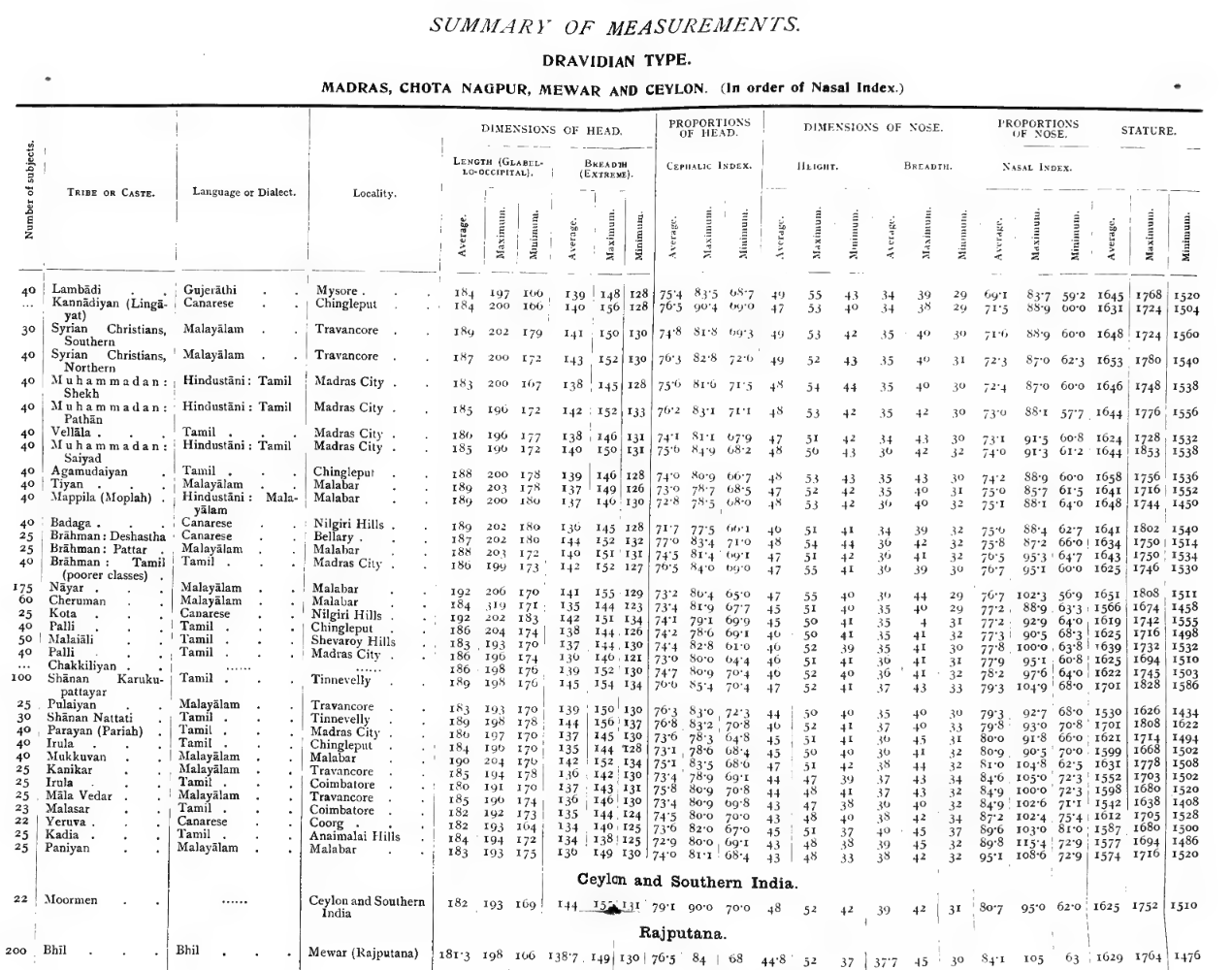

Source: H.H. Risley, The People of India, 1908

Herbert Hope Risley (1851–1911) served as Census Commissioner for the 1901 Census of India. Risley developed an elaborate system of racial classification based on anthropometric measurements, including his nasal indexநாசி குறியீடுNasal IndexRatio of nose width to length — pseudoscientific measurement Risley used to rank Indian "races."—the ratio of nose width to nose length—which he used to rank Indian populations on a hierarchy from Aryanஆரியன்ĀryanColonial racial category for "noble" northern Indians — now discredited as pseudoscience. to Dravidianதிராவிடர்DrāviḍarColonial racial category for southern Indians — originally a linguistic term, racialized by British ethnographers..

Bernard S. Cohn demonstrates that colonial categories—particularly caste classifications in the census—did not simply describe existing social structures but actively reshaped them. The census made caste "objective" in ways it had never been before.

— Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge, Princeton University Press, 1996

Moroccan and Indian Scholarly Perspectives

Scholars from formerly colonized societies have offered crucial analyses of how colonial knowledge production operated.

Abdallah Laroui (b. 1933), the Moroccan historian and philosopher, addresses French colonial knowledge in The History of the Maghrib: An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University Press, 1977), analyzing how French ethnographic categories distorted North African history and self-understanding.

"It was not enough to drive the Maghribi once again beyond the limes into the desert of camels, palm trees and zawiyasزاويةzāwiyaSufi religious lodge; center for Islamic education, spiritual practice, and community gathering., it was necessary also to deprive him of his religion, language and historic heritage, so producing a man free from culture, who could then be civilized.

— Abdallah Laroui, The history of the Maghrib: An Interpretative Essay, 1977

The Indian political theorist Partha Chatterjee (b. 1947) has examined how colonial knowledge categories were sometimes adopted, sometimes resisted, and sometimes transformed by nationalist movements in The Nation and Its Fragments (Princeton University Press, 1993).

The sociologist M.N. Srinivas (1916–1999) documented how British census categories influenced caste consciousness in India, contributing to both rigidification and political mobilization around caste identity.

Knowledge and Power

What connects the French ethnographer documenting Berber customary law with the British census commissioner measuring skulls in Bengal? Both operated on the premise that knowledge precedes and enables rule. To classify a population is to make it governable. To create categories—Arab/Berber, Aryan/Dravidian, martial race/non-martial race—is to create the tools of administration.

Burke, Edmund III. The Ethnographic State: France and the Invention of Moroccan Islam. UC Press, 2014.

Cohn, Bernard S. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge. Princeton UP, 1996.

Risley, H.H. The People of India. Thacker, Spink & Co., 1908.

Laroui, Abdallah. The History of the Maghrib. Princeton UP, 1977.

Archives Marocaines (1904–1912). Digitized via Gallica/BNF.

The Division

"Under colonialism, caste was thus made out to be far more—far more pervasive, far more totalizing, far more uniform— than it had ever been before."

— Nicholas B. Dirks, Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India (2001)

Colonial powers sought to divide as much as to know. Across Morocco and India, European administrators created ethnic and social classifications that fractured indigenous societies along lines that often had little basis in lived reality.

These divisions served as political technologies designed to prevent unified resistance. By elevating some groups and subordinating others, by hardening fluid identities into fixed categories, colonialism created hierarchies that would long outlast formal colonial rule.

Morocco: The Berber Dahir of 1930

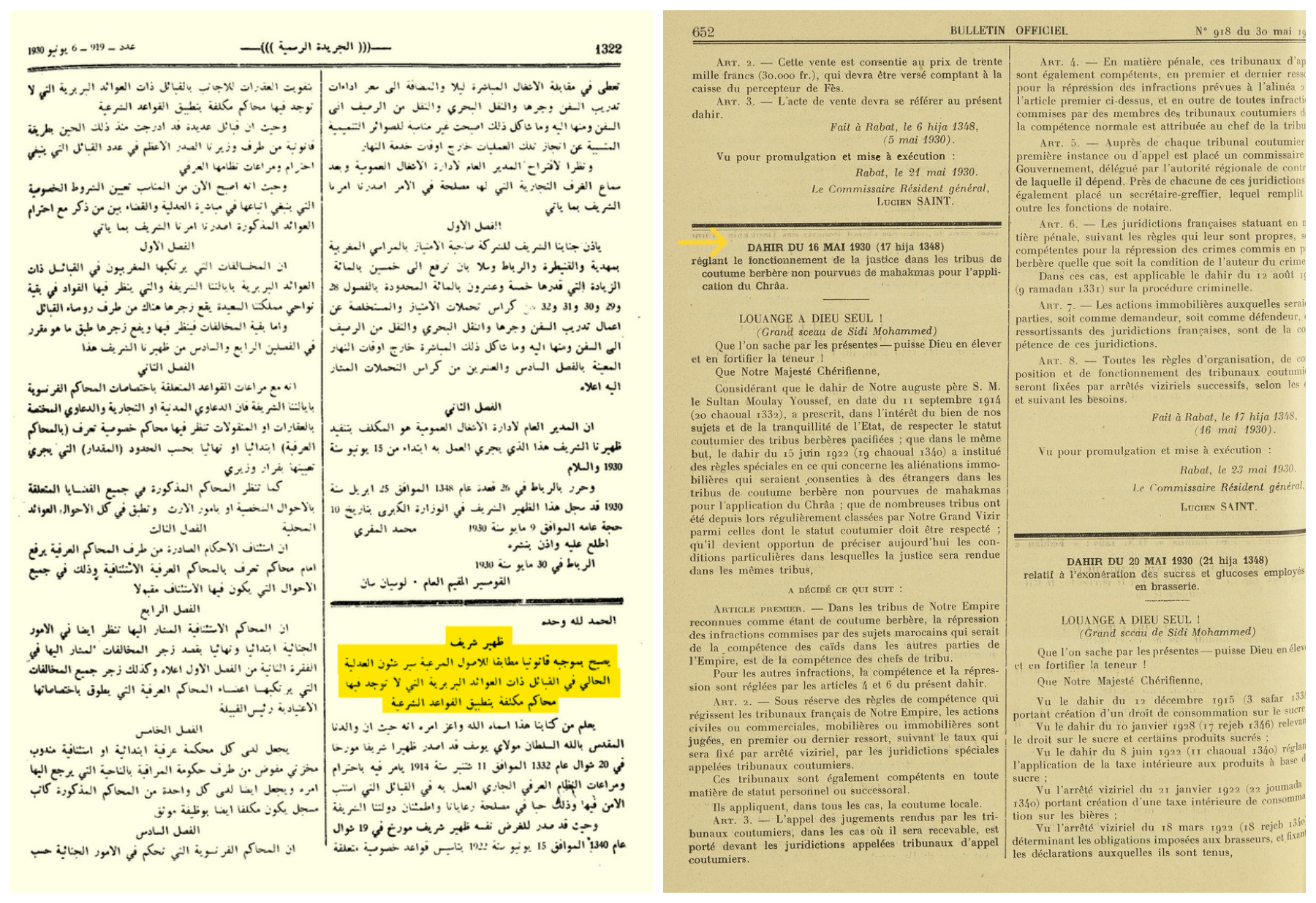

On May 16, 1930, the French Residency in Morocco issued a royal decree—a dahirظهيرẒahīrRoyal decree issued by the Moroccan Sultan — under the Protectorate, often drafted by French administrators.—that would ignite the first mass nationalist movement in Moroccan history.

The Berber Dahir (Dahir Berbère) placed Berber-speaking tribes under French customary law and French judicial courts, removing them from the jurisdiction of Shariaالشريعةal-SharīʿaIslamic law derived from the Quran and Hadith — the Berber Dahir aimed to sever Berbers from this shared legal tradition. and the Sultan's religious authority. On its surface, the decree claimed to respect Berber "traditional customs." In practice, it aimed to sever Berbers from the Arab-Islamic identity that unified Morocco.

Source: Internet archive

The Berber Dahir, published in the "Bulletin Officiel du Protectorat de la République Française au Maroc", No. 918, May 23, 1930.

Source: Bibliothèque Diplomatique Numérique

The policy reflected decades of French politique berbèreالسياسة البربريةPolitique Berbère"Berber policy" — French colonial strategy to separate Berbers from Arabs, portraying them as closer to Europeans and less Muslim., which held that Berbers were racially and culturally distinct from Arabs—closer to Europeans, less attached to Islam, and therefore more amenable to French civilization.

"Passant par transitions souvent rapides des prescriptions d'un droit coutumier singulièrement primitif — bien que très vivant et merveilleusement adapté parfois aux circonstances économiques de l'existence — aux règles rigides établies par la législation sacrée du Coran, les Berbères voient ainsi se précipiter, après leur soumission, la ruine des traditions auxquelles ils sont secrètement le plus attachés."

Robert Montagne's Les Berbères et le Makhzen dans le Sud du Maroc (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1930), published the same year as the Dahir, provided ethnographic justification for separate Berber administration, presenting the Arab-Berber distinction as ancient and essential.

— Robert Montagne, Les Berbères et le Makhzen dans le Sud du Maroc, 1930

Education as Division

While the Dahir was the public face of division, the deeper work happened in secret. The French administration created a completely separate school system for Berbers, deliberately hidden from the Sultan and his Moroccan administrators.

In an internal memo dated June 25, 1924, Marshal Lyautey stated his intentions explicitly. The goal of separate Berber schools was to "tame the indigène, and to maintain—discreetly, but as firmly as possible—the linguistic, religious, and social differences that exist between the Arabized bled makhzenبلاد المخزنbilād al-makhzanTerritories under direct control of the Sultan's government; contrasted with "bled siba" (lands of dissidence). and the Berber mountains, which, while religious, are pagan and ignorant of Arabic."

Source: dafina.net forums (shared by lamgaz, 31 January 2015). Photograph c. 1929.

The flagship institution was the Collège Berbère d'Azrou, founded in 1927 in the Middle Atlas. French and Berber (written in Latin script) served as languages of instruction; Arabic was rigorously prohibited, with no Quranic education at the primary level. The goal: produce a Francophone Berber administrative class severed from Arab-Islamic culture. By 1950, 250 of Morocco's 350 official caïds were Azrou graduates.

Yet the strategy backfired. In February 1944, students at Azrou went on strike in solidarity with the nationalist movement—a direct refutation of the colonial logic that had created their school.

The Colonial Construction of "Arab" versus "Berber"

French ethnographers constructed a sharp binary between "Arab" and "Berber" populations that mapped onto a moral hierarchy:

FRENCH VIEW OF "BERBER"

- — "Indigenous" to North Africa

- — Pre-Islamic, pagan roots

- — Democratic, tribal

- — Racially closer to Europeans

- — Amenable to French civilization

FRENCH VIEW OF "ARAB"

- — "Invaders" from Arabia

- — Fanatically Muslim

- — Despotic, feudal

- — Racially Semitic

- — Resistant to progress

This binary obscured the reality of Moroccan society, where Arab and Berber identities were fluid, intermarried, and united by Islam. Many Moroccans spoke both Arabic and Tamazight. The distinction between Bled Makhzenبلاد المخزنBled al-MakhzenLands under central government authority. (lands under central authority) and Bled Sibaبلاد السيبةBled al-Siba"Land of dissidence" — areas outside central control, but not lawless. (lands outside central control) was similarly distorted by French administrators who portrayed it as an eternal, racial divide rather than a shifting political relationship.

Abdallah Laroui critiques colonial historiography's treatment of the Arab-Berber distinction, arguing that French scholars imposed categories foreign to Maghribi self-understanding—categories designed to divide rather than describe.

— Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib, Princeton UP, 1977

India: Caste as Colonial Category

In India, the British did not invent caste—but they transformed it. What had been a fluid, regional, and contextual system of social organization became, under colonial rule, a rigid, enumerated, and all-India hierarchy.

The decennial census, beginning in 1871, required colonial administrators to classify every Indian by caste. This seemingly neutral act of enumeration had profound consequences:

Fixing fluid categories: Local jatisசாதிJātiBirth group — occupational/kinship communities, often local and fluid. (occupational/kinship groups) were forced into standardized all-India varnaவர்ணம்VarnaThe four-fold textual classification — a Brahmanical ideal, not lived reality. categories.

Creating hierarchy: Herbert Hope Risley's 1901 Census ranked castes by "social precedence," creating official hierarchies where ambiguity had existed.

Enabling mobilization: Once caste became an official category, groups organized to improve their census ranking—making caste more politically salient than ever before.

Herbert Hope Risley (1851–1911) was the most influential architect of colonial caste classification. As Census Commissioner for the 1901 Census, he implemented a system that ranked castes based on how much "respect" higher castes showed them—essentially codifying social prejudice as scientific fact. His work also incorporated anthropometric theories, using measurements like the "nasal index" to argue that caste distinctions reflected racial differences between "Aryan" and "Dravidian" populations.

Nicholas B. Dirks argues that caste as we know it today is substantially a colonial creation. British administrators, missionaries, and ethnographers made caste the central organizing principle of Indian society in ways that had not been true before colonial rule.

— Nicholas B. Dirks, Castes of Mind, Princeton UP, 2001

The "Martial Races" Theory

Beyond caste, British administrators developed the theory of martial racesபோர் இனங்கள்Martial RacesBritish theory that some Indian communities (Sikhs, Gurkhas, Pathans) were "naturally" warlike — a political fiction created after 1857.—the idea that some Indian communities were naturally warlike and loyal, while others were effeminate and untrustworthy.

After the 1857 Revolt1857 புரட்சிSepoy Mutiny / First War of IndependenceMajor uprising against British rule — called "Mutiny" by the British, "First War of Independence" by Indians., in which Bengali sepoys played a major role, the British restructured the Indian Army to favor Sikhs, Gurkhas, Pathans, and Punjabi Muslims—groups deemed "martial"—while excluding Bengalis, Marathas, and South Indians. The theory had no scientific basis. It was a political response to 1857, designed to recruit from communities considered loyal and exclude those considered dangerous.

Parallel Strategies, Parallel Consequences

The French in Morocco and the British in India pursued strikingly similar divide-and-rule strategies:

MOROCCO

- — Arab vs. Berber

- — Berbers as "less Muslim"

- — Berber Dahir (1930): separate legal systems

- — Bled Makhzen vs. Bled Siba as eternal divide

INDIA

- — Hindu vs. Muslim

- — "Martial races" as more loyal

- — Separate electorates (1909): separate political systems

- — Caste as unchanging essence

In both cases, colonial administrators took fluid, contextual identities and fixed them into rigid categories. These categories were presented as ancient and natural, obscuring their recent, political origins. The categories created real consequences—legal, economic, social—that made them self-fulfilling.

The Violence of Classification

Classification was never innocent. To be labeled "Berber" in French Morocco meant being subject to French courts rather than Islamic law. To be enumerated as a "depressed class" in British India meant being marked as inferior. To be excluded from "martial race" status meant being denied military employment.

Colonial categories created what Arjun Appadurai has called "enumerated communities"—groups that became conscious of themselves as groups precisely through the process of being counted and classified.

— Arjun Appadurai, "Number in the Colonial Imagination," in Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament, 1993

Berber Dahir. Bulletin Officiel du Protectorat, No. 918, May 23, 1930.

Dirks, Nicholas B. Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Princeton UP, 2001.

Risley, H.H. The People of India. Thacker, Spink & Co., 1908.

Montagne, Robert. Les Berbères et le Makhzen dans le Sud du Maroc. Félix Alcan, 1930.

Laroui, Abdallah. The History of the Maghrib. Princeton UP, 1977.

Bayly, Susan. Caste, Society and Politics in India. Cambridge UP, 1999.

Resistance

"The French sought to divide Morocco into two races. The Moroccan people answered with one voice."

— Framing the Ya Latif protests of 1930

Colonial strategies of division were designed to prevent unified resistance. They often achieved the opposite. By attempting to sever communities from their shared identities—religious, cultural, national—colonial powers inadvertently created the conditions for mass mobilization.

This chapter traces two moments when divide-and-rule backfired: the Ya Latifيا لطيفYā Laṭīf"O Gentle One" — one of the 99 names of God in Islam, invoked in the 1930 protests against the Berber Dahir. protests against the Berber Dahir in Morocco (1930), and the 1857 Revolt1857 புரட்சிFirst War of IndependenceMajor uprising against British rule — called "Sepoy Mutiny" by the British, "First War of Independence" by Indian nationalists. in India. In both cases, colonial classifications meant to fragment became rallying points for unity.

Morocco: The Ya Latif Protests (1930)

The Berber Dahir of May 16, 1930, was intended to quietly separate Berber populations from Arab-Islamic Morocco. Instead, it ignited the first mass nationalist movement in Moroccan history.

Within weeks of the Dahir's publication, protests erupted across Morocco. The movement took a distinctive form: collective recitation of the Latif Prayer in mosques. Ya Latif—"O Gentle One"—is one of the ninety-nine names of God in Islam, traditionally invoked in times of calamity.

يا لطيف، نسألك اللطف فيما جرت به المقادير، لا تفرق بيننا وبين إخواننا البرابر

"O Gentle One, we ask Your gentleness in what fate has decreed.

Do not separate us from our Berber brothers."

— The Latif Prayer, recited in Moroccan mosques, 1930

The Significance of Ya Latif

The choice of the Latif Prayer was strategically brilliant. By framing resistance as religious supplication rather than political protest, Moroccan nationalists:

United Arab and Berber Muslims under a shared Islamic identity—precisely what the French had tried to sever. Made repression difficult for the French, who could not easily ban prayer in mosques. Mobilized women and the uneducated, who might not attend political meetings but did attend mosque. Created a decentralized movement that spread through existing religious networks.

The protests spread beyond Morocco. In Paris, North African workers and students organized solidarity actions. In Egypt, the prominent journal Al-Fath published articles condemning the Dahir, internationalizing the issue across the Arab world.

Jonathan Wyrtzen argues that the Berber Dahir crisis was a turning point in Moroccan political consciousness—the moment when colonial categories intended to divide instead created a unified nationalist response.

— Jonathan Wyrtzen, Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity, Cornell UP, 2015

Key Figures in Moroccan Nationalism

Allal al-Fassiعلال الفاسيʿAllāl al-Fāsī(1910–1974) Founder of Moroccan nationalism, later leader of the Istiqlal (Independence) Party. (1910–1974): One of the founders of Moroccan nationalism, later leader of the Istiqlalالاستقلالal-Istiqlāl"Independence" — Moroccan nationalist party founded in 1944, emerged from the 1930 protests. (Independence) Party. Al-Fassi was arrested multiple times for his role in organizing resistance.

Mohammed Hassan al-Ouazzani (1910–1978): Journalist and nationalist leader who helped publicize the Dahir crisis internationally.

Ahmed Balafrej (1908–1990): Co-founder of the nationalist movement who helped organize the Paris-based protests.

India: The 1857 Revolt

Twenty-seven years before the Berlin Conference formalized the "Scramble for Africa," India experienced the largest armed resistance to European colonialism in the nineteenth century.

The Revolt of 1857—called the "Sepoy Mutiny" by the British, the "First War of Independence" by Indian nationalists—began as a military uprising and expanded into a widespread civilian rebellion across North India.

Immediate trigger: Sepoysசிப்பாய்SipāhīIndian soldiers serving in the British East India Company's army. (Indian soldiers in the British Indian Army) refused to use new rifle cartridges rumored to be greased with cow and pig fat—offensive to both Hindus and Muslims. But the cartridge issue was merely a spark; the fuel was decades of accumulated grievances.

Unity Across Division

What alarmed the British most about 1857 was the cooperation between communities they had assumed were permanently divided.

The rebels proclaimed Bahadur Shah Zafarபகதூர் ஷாBahādur Shāh Ẓafar(1775–1862) Last Mughal emperor, made symbolic leader of the 1857 Revolt. Died in exile in Rangoon. (1775–1862), the aged Mughal emperor, as their symbolic leader—a Muslim figurehead supported by Hindu and Muslim soldiers alike.

"It is well known that in these days all the English have entertained these evil designs... it is further necessary that all Hindus and Mussalmans unite in this struggle."

— Proclamation issued at Delhi, 1857 (verify in Rizvi & Bhargava, Freedom Struggle in Uttar Pradesh, London Times, 31 August 1857)

The Rani of Jhansi, Lakshmibai (1828–1858), became one of the revolt's most celebrated leaders—a Hindu queen fighting alongside Muslim soldiers. In Lucknow, Awadh's Muslim nobility and Hindu merchants cooperated in resistance.

British Response: Intensified Division

The British suppression of 1857 was brutal—mass executions, destruction of villages, collective punishment. But the longer-term response was equally significant: a deliberate intensification of divide-and-rule policies.

After 1857, British administrators concluded that they had allowed Indians to become too unified. Future policy would emphasize: Religious division through separate electorates and institutions; the "martial races" theory recruiting from communities deemed loyal while excluding those associated with rebellion; and princely state cultivation, supporting loyal Indian princes as buffers against nationalist sentiment.

Thomas R. Metcalf examines how 1857 transformed British policy—the revolt convinced administrators that India could only be ruled through deliberate cultivation of communal division.

— Thomas R. Metcalf, The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857–1870, Princeton UP, 1964

Parallel Patterns

Both the Ya Latif protests and the 1857 Revolt reveal a recurring pattern: colonial attempts to divide populations often created the very unity they sought to prevent.

MOROCCO (1930)

- — Ya Latif prayer united Arab and Berber Muslims

- — Religious framework made repression difficult

- — International solidarity from Arab world

- — French forced to retreat from politique berbère

INDIA (1857)

- — Rebel proclamations called for Hindu-Muslim unity

- — Mughal emperor as shared symbolic leader

- — Cross-community military cooperation

- — British intensified division policies after

The Dialectic of Division and Unity

The Berber Dahir, by threatening to sever Berbers from Islam, demonstrated to all Moroccans—Arab and Berber alike—that they shared a common identity worth defending. The British attempt to maintain separate Hindu and Muslim grievances in 1857 failed when both communities recognized a common enemy.

This does not mean colonial division was ineffective. In the long run, communal categories hardened. The partition of India in 1947 and ongoing ethnic tensions in postcolonial states testify to the lasting damage of colonial classification.

But the moments of resistance remind us that division was never total, never uncontested. The colonized were not passive recipients of colonial categories. They adapted, resisted, and sometimes turned those categories against their creators.

Halstead, John P. Rebirth of a Nation: The Origins and Rise of Moroccan Nationalism. Harvard UP, 1967.

Wyrtzen, Jonathan. Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity. Cornell UP, 2015.

Metcalf, Thomas R. The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857–1870. Princeton UP, 1964.

Mukherjee, Rudrangshu. Awadh in Revolt, 1857–1858. Oxford UP, 1984.

Guha, Ranajit. Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India. Oxford UP, 1983.

Bodies of Art

"The colonized is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country's cultural standards."

— Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

Colonial rule did not only classify territories and populations—it classified bodies. Across Morocco and India, European administrators and missionaries encountered female performers whose art intertwined the sacred and the sensual. These women—the Shikhateالشيخاتal-ShīkhātProfessional female singer-dancers of Morocco, practitioners of Aïta poetry. of Morocco and the DevadasisதேவதாசிDevadāsi"Servant of god" — women ritually dedicated to Hindu temples as dancers and custodians of classical arts. of India—became targets of colonial morality campaigns that would reshape indigenous attitudes toward gender, sexuality, and performance.

This chapter traces how Victorian moral frameworks, imposed through colonial law and missionary pressure, transformed respected artists into figures of shame—a transformation whose effects persist into the present day.

India: The Devadasis

The word Devadasi (தேவதாசி) means "servant of god." For centuries, devadasis were women ritually dedicated to Hindu temples, where they performed sacred dances, maintained the temple, and served as custodians of classical arts.

Devadasis occupied a complex social position. They were ritually married to the deity, making them nityasumangaliநித்யசுமங்கலிNityasumaṅgalī"Ever-auspicious woman" — a devadasi could never be widowed, as her divine husband was immortal.—"ever-auspicious" women who could never be widowed. They were custodians of classical dance, economically independent, and outside conventional marriage—which granted them freedoms unavailable to married women.

The dance they performed, Sadhirசதிர்SadirOriginal temple dance tradition, later "sanitized" and renamed Bharatanatyam in the 20th century., was a sophisticated art form incorporating Shringaraசிருங்காரம்ŚṛṅgāraThe erotic sentiment — one of the nine rasas (aesthetic emotions) in classical Indian theory. In temple context, it represented devotion through divine love.—the erotic sentiment—as one of its essential aesthetic components. In Hindu temple theology, erotic devotion to the deity was not scandalous but sacred.

Saskia Kersenboom's foundational study documents how devadasis were not merely dancers but ritual specialists whose presence was essential to temple function—their "ever-auspicious" status made them indispensable for ceremonies where widows were forbidden.

— Saskia Kersenboom, Nityasumangali: Devadasi Tradition in South India, Motilal Banarsidass, 1987

The Anti-Nautch Movement

British missionaries and colonial administrators viewed devadasi traditions through the lens of Victorian sexual morality. What they saw scandalized them: women dancing in temples, women outside marriage, women whose art celebrated erotic sentiment.

The Anti-Nautch Movement emerged in the 1890s, led by an alliance of British missionaries and Indian social reformers. "Nautch" (from the Hindi nāch, meaning dance) became a term of disapproval applied to all Indian dance traditions.

"These nautch parties have the effect of lowering

the English character in the eyes of the natives."

— Anti-Nautch petition to the Governor of Madras, 1893

The movement framed devadasis as prostitutes, erasing the distinction between sacred performance and sex work. This framing would have lasting consequences.

Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi and Abolition

The campaign against devadasis was not solely a colonial imposition. Indian reformers—particularly upper-caste women influenced by Victorian morality—played a central role.

Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi (1886–1968), the first woman legislator in British India, led the campaign for abolition. In 1927, she introduced a bill in the Madras Legislative Council to end temple dedication of girls. The Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act was finally passed in 1947, the year of Indian independence. It criminalized the dedication of girls to temples and effectively abolished the devadasi institution.

Davesh Soneji documents how devadasi families experienced abolition not as liberation but as loss—loss of livelihood, loss of status, loss of artistic tradition. His oral histories reveal women who remember being told their entire way of life was now criminal.

— Davesh Soneji, Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India, University of Chicago Press, 2012

Morocco: The Shikhate

The Shikhate (الشيخات, singular: Shikha) are professional female singer-dancers of Morocco, practitioners of Aïtaالعيطةal-ʿAyṭa"The cry" — Moroccan oral poetry tradition performed at festivals and gatherings. Themes include love, loss, social commentary, and resistance. (العيطة)—a genre of oral poetry that has been called "the cry of the Moroccan land."

Aïta originated as rural folk poetry, performed at festivals, weddings, and community gatherings. Its themes include love, loss, social commentary, and resistance. During the colonial period, Shikhate performed songs that encoded anticolonial sentiment.

The Shikha occupied a social position both celebrated and stigmatized: custodians of oral tradition, public performers in a society where respectable women remained private, economically independent, and often living outside conventional marriage.

Deborah Kapchan's ethnography documents how the Shikha navigates between stigma and celebration—how the same woman can be honored as a poet at a rural festival and condemned as immoral in the city.

— Deborah Kapchan, Gender on the Market: Moroccan Women and the Revoicing of Tradition, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996

Colonial Classification of Moroccan Music

French colonial musicologists approached Moroccan music with the same taxonomic impulse they applied to populations. Alexis Chottin (1891–1976), a French musicologist who worked in Morocco, produced influential studies that classified Moroccan music into hierarchies.

Chottin's Tableau de la Musique Marocaine (1939) distinguished "refined" urban music (Andalusian traditions, associated with civilization) from "primitive" rural music (including Aïta, associated with the uncivilized). This classification mapped onto colonial hierarchies: Arab/urban/civilized versus Berber/rural/primitive. The Shikhate, as practitioners of rural traditions and as women who performed publicly, occupied the lowest rung.

Colonial Morality and the Shikha's Body

French colonial authorities and Moroccan urban elites (influenced by both colonial and reformist Islamic discourse) increasingly stigmatized the Shikhate. The concept of FitnaفتنةFitnaOften translated as "chaos" or "temptation" — carries connotations of social disorder caused by female sexuality. Used to stigmatize women's public presence. (فتنة)—often translated as "chaos" or "temptation," but carrying connotations of social disorder caused by female sexuality—was deployed against the Shikhate. Their public presence, their unveiled faces, their dancing bodies were framed as threats to social order.

The stigmatization of the Shikhate cannot be attributed solely to colonialism. Pre-colonial discourse also contained ambivalent attitudes toward female performers. But colonialism intensified and codified this stigmatization, transforming fluid social attitudes into fixed moral categories.

Parallel Patterns

Despite vast differences in religious context, the Devadasi and Shikhate faced strikingly similar fates under colonialism:

DEVADASI (INDIA)

- — Temple dancers, "servants of god"

- — Ritually married to deity

- — Economically independent

- — Custodians of Sadhir dance

- — Art included Shringara (erotic sentiment)

- — Targeted by Anti-Nautch movement

- — Legally abolished (1947)

- — Term became slur: "Thevadiya"

SHIKHATE (MOROCCO)

- — Festival performers, poets of Aïta

- — Outside conventional marriage

- — Economically independent

- — Custodians of oral poetry

- — Art included themes of love and desire

- — Targeted by colonial/reformist morality

- — Socially stigmatized (not legally abolished)

- — Term became insult in Darija

The Sacred and the Sensual

Both traditions challenge a distinction that Victorian morality took for granted: the separation of the sacred from the sensual.

In Hindu temple theology, erotic devotion (bhakti infused with shringara) was a legitimate path to the divine. The poet-saint Andalஆண்டாள்Āṇṭāḷ8th-century Tamil poet-saint who wrote passionate love poetry addressed to Vishnu. Her works are still recited in temples today. (ஆண்டாள், 8th century CE) wrote passionate love poetry addressed to Vishnu—poetry still recited in temples today. In Moroccan Sufi tradition, ecstatic practices including music and dance were pathways to divine experience.

Colonial morality could not accommodate these traditions. The dancing body was either sacred OR sensual—never both. By imposing this binary, colonialism fundamentally altered indigenous relationships to art, spirituality, and the body.

Ann Laura Stoler demonstrates how colonial regimes governed not only territories but intimacies—sexuality, domesticity, the body itself became sites of colonial regulation and racial anxiety.

— Ann Laura Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power, University of California Press, 2002

Voices of the Performers

One of the challenges in writing this history is the scarcity of first-person accounts from devadasis and shikhate themselves. Colonial and reformist archives are full of voices speaking about these women; voices of these women are harder to find.

Davesh Soneji's Unfinished Gestures is significant precisely because it centers the oral histories of devadasi descendants—women who remember the abolition and its aftermath from within their communities. These testimonies reveal experiences of abolition not as liberation but as dispossession.

Soneji, Davesh. Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Kersenboom, Saskia. Nityasumangali: Devadasi Tradition in South India. Motilal Banarsidass, 1987.

Kapchan, Deborah. Gender on the Market: Moroccan Women and the Revoicing of Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

Chottin, Alexis. Tableau de la Musique Marocaine. Paul Geuthner, 1939.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power. University of California Press, 2002.

Sanitization

"It's essentially an upper-caste woman appropriating the arts and culture of lower-caste women and taking ownership of the dance form."

— Abirami, on the transformation of Sadhir into Bharatanatyam

Colonialism did not only suppress indigenous arts—it transformed them. In both Morocco and India, traditional performance practices were subjected to processes of "sanitization": the removal of elements deemed immoral, primitive, or embarrassing by colonial and nationalist elites.

This chapter traces how Sadhirசதிர்SadirOriginal temple dance performed by devadasis, later "sanitized" and renamed Bharatanatyam. became Bharatanatyamபரதநாட்டியம்Bharatanāṭyam"Classical" dance created from Sadhir in the 1930s–40s. The name claims Sanskrit/pan-Indian lineage, erasing the Tamil devadasi context. in India, and how French musicologists created hierarchies that separated "refined" from "primitive" Moroccan music. In both cases, sanitization involved erasing the contributions of the very communities who had created and preserved these traditions.

India: From Sadhir to Bharatanatyam

The dance that devadasis performed in temples was called Sadhir (சதிர்) or Dasi Attam (தாசி ஆட்டம், "dance of the dasi"). By the mid-twentieth century, this dance had been transformed into Bharatanatyam—a "classical" art form stripped of its temple context, its erotic elements, and its association with devadasi communities.

The Revival Movement

In the 1930s, as the Anti-Nautch movement succeeded in stigmatizing devadasi traditions, a counter-movement emerged that sought to "save" Indian dance by separating it from the women who performed it.

E. Krishna Iyer (1897–1968), a lawyer and freedom fighter, championed the revival of Indian dance. He performed Sadhir himself (dressed as a woman) to demonstrate that dance could be respectable, advocating for dance to be taught in schools and performed in concert halls rather than temples.

Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904–1986), a Brahmin woman, became the most influential figure in the transformation. In 1936, she founded Kalakshetraகலாக்ஷேத்ராKalākṣetra"Temple of art" — institution founded by Rukmini Devi in 1936 that became the center of the new "classical" Bharatanatyam., an arts institution in Madras that would become the center of the new "classical" dance.

What Changed: The Sanitization of Dance

Rukmini Devi's Bharatanatyam differed from devadasi Sadhir in significant ways:

SADHIR (DEVADASI TRADITION)

- — Performed in temples

- — Ritual/devotional function

- — Hereditary practice (devadasi families)

- — Shringara (erotic sentiment) central

- — Costumes allowed sensual movement

- — Repertoire included explicit love poetry

- — Addressed to the deity

BHARATANATYAM (REVIVAL)

- — Performed on proscenium stages

- — Aesthetic/cultural function

- — Taught to upper-caste women

- — Shringara minimized or spiritualized

- — Costumes restricted movement

- — "Objectionable" items removed

- — Addressed to audience

The dance scholar Avanthi Meduri documents how the revival involved a fundamental recontextualization—the same movements now meant something entirely different when performed by Brahmin women on concert stages rather than by devadasis in temples.

— Avanthi Meduri, "Bharatha Natyam—What Are You?" Asian Theatre Journal, 1988

The Erasure of Devadasi Contributions

The revival did not acknowledge its debt to devadasi teachers. Upper-caste women learned from devadasi masters, then presented the dance as a recovered "classical" tradition belonging to Hindu civilization broadly—not to the specific communities who had preserved it.

T. Balasaraswati (1918–1984), a devadasi-lineage dancer, offered an alternative vision. Unlike Rukmini Devi, Balasaraswati maintained the centrality of shringara and resisted the spiritualization of erotic content. Her approach represented continuity with devadasi practice, but it was Rukmini Devi's sanitized version that became dominant.

Davesh Soneji documents how devadasi families experienced the revival not as celebration but as theft—their art was taken and transformed, while they themselves remained stigmatized.

— Davesh Soneji, Unfinished Gestures, University of Chicago Press, 2012

The Renaming: Why "Bharatanatyam"?

The name change was significant. "Sadhir" and "Dasi Attam" referenced the devadasi context. "Bharatanatyam" claimed a different lineage: Bharata (the sage who authored the ancient Natyashastra) + Natyam (dance). The new name located the dance in a Sanskritic, pan-Indian classical tradition rather than in the specific Tamil temple context where it had actually been practiced.

Morocco: The Classification of Music

French colonial musicologists approached Moroccan music with taxonomic zeal, creating hierarchies that would shape how Moroccans themselves understood their musical heritage.

Alexis Chottin (1891–1976) was the most influential of these musicologists. His Tableau de la Musique Marocaine (1939) classified Moroccan music into categories that mapped onto colonial valuations:

CHOTTIN'S HIERARCHY OF MOROCCAN MUSIC

| Andalusian music (al-Āla) | "Refined," urban, civilized |

| Religious music (Sufi) | Interesting but "fanatical" |

| Berber music | "Primitive," rural, authentic |

| Popular urban music (Aïta, Malhun) | "Vulgar," morally suspect |

The Elevation of Andalusian Music

French and Moroccan elites agreed on one thing: Andalusian musicالآلةal-ĀlaAndalusian classical music tradition, associated with refugees from Spain after 1492. Elevated as Morocco's "high" culture by colonial and postcolonial authorities. (al-Āla) represented the pinnacle of Moroccan musical civilization. This tradition, associated with Muslim refugees who fled Spain after 1492, was urban, courtly, and—crucially—could be connected to a narrative of civilizational exchange with Europe.

After independence (1956), the Moroccan state continued to privilege Andalusian music. Conservatories were established to preserve it. Festival programs featured it prominently. It became the "classical" music of Morocco—analogous to Bharatanatyam's status in India.

The Devaluation of Aïta

While Andalusian music was elevated, traditions like Aïta were devalued. Chottin's taxonomy placed Aïta at the bottom—"popular," "vulgar," associated with the morally suspect Shikhate.

This classification had real consequences: Aïta was excluded from conservatory curricula, state cultural institutions did not support it, performers continued to face social stigma, and the tradition was not documented or preserved with the same care as "classical" forms.

Ahmed Aydoun, a Moroccan musicologist, has worked to recuperate traditions marginalized by colonial and postcolonial hierarchies, documenting the sophistication of forms dismissed as "vulgar."

— Ahmed Aydoun, Musiques du Maroc, Eddif, 1992

Parallel Patterns

The sanitization of performance traditions in India and Morocco followed similar logics:

INDIA

- — Sadhir → Bharatanatyam

- — Devadasi contribution erased

- — Upper-caste women became custodians

- — Shringara (erotic) minimized

- — Kalakshetra as institutional center

- — Sanskrit/"classical" framing

- — Nationalist "Indian civilization" narrative

MOROCCO

- — Diverse traditions → Andalusian as "classical"

- — Shikhate contribution marginalized

- — Urban elites became arbiters of taste

- — "Vulgar" popular traditions devalued

- — Conservatories privilege Andalusian

- — Andalusian/courtly framing

- — Nationalist "Moroccan heritage" narrative

The Violence of Respectability

Sanitization was not preservation—it was transformation. The "classical" arts that emerged from these processes were genuinely beautiful and meaningful. But they were not the same as what had existed before.

What was lost: The ritual context that gave performances their meaning. The communities whose hereditary knowledge was appropriated. The aesthetic elements deemed "objectionable" by reformers. The economic systems that had supported performers. The theological frameworks that united sacred and sensual.

What was gained: A "respectable" national art form. Access to performance for upper-caste/elite women. International recognition as "classical" traditions. Preservation (in transformed form) when outright abolition threatened.

The question of whether sanitization was net positive or negative admits no easy answer. But it is essential to recognize that the "classical" traditions celebrated today are products of specific historical processes—not timeless essences recovered from an ancient past.

Soneji, Davesh. Unfinished Gestures. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Meduri, Avanthi. "Bharatha Natyam—What Are You?" Asian Theatre Journal 5, no. 1 (1988).

Chottin, Alexis. Tableau de la Musique Marocaine. Paul Geuthner, 1939.

Allen, Matthew Harp. "Rewriting the Script for South Indian Dance." TDR 41, no. 3 (1997).

Aydoun, Ahmed. Musiques du Maroc. Eddif, 1992.

Colonial Memory

"There was a period in my life where I so desperately wanted English to be my mother tongue."

— Abirami

Colonialism did not end with independence. Its categories, its aesthetics, its ways of seeing persisted—internalized by the formerly colonized, commodified for global consumption, embedded in languages and institutions.

This chapter examines how colonial frameworks continue to shape memory and identity in postcolonial Morocco and India. From the nostalgic gaze of heritage tourism to the internalization of colonial shame, the past is never simply past.

The Persistence of Colonial Categories

The categories invented by colonial administrators—Berber/Arab, caste hierarchies, "martial races," "classical" versus "folk"—did not disappear with independence. They were inherited by postcolonial states, embedded in census forms, educational curricula, and cultural policies.

India: Independent India retained the colonial census apparatus, continuing to enumerate populations by caste and religion. The categories created by Risley and his successors became the basis for affirmative action policies (reservations), making colonial classifications legally and politically consequential in new ways.

Morocco: The French distinction between "Arab" and "Berber" continued to shape Moroccan politics after 1956. Though the nationalist movement had rejected the politique berbère, tensions around Amazighⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖ / الأمازيغImazighenIndigenous peoples of North Africa, often called "Berber" (a term some reject as colonial). The Amazigh movement seeks cultural and linguistic recognition. (Berber) identity and Arabizationالتعريبal-TaʿrībPostcolonial policy promoting Arabic over French and Amazigh languages. Itself a reaction to colonialism, it sometimes marginalized Amazigh speakers. policies persisted for decades.

Colonial Nostalgia

A peculiar phenomenon of the postcolonial era is the nostalgia for colonialism—not among the colonizers, but among some of the colonized.

Heritage Tourism: Colonial-era buildings, hill stations, and "heritage hotels" are marketed as romantic destinations. The violence that built these structures is erased; what remains is aesthetic charm. In India, former British clubs and railway stations attract tourists seeking "Raj nostalgia." In Morocco, French-built villes nouvelles and Art Deco architecture are celebrated as heritage.

Renato Rosaldo coined the term "imperialist nostalgia" to describe how colonizers mourn the passing of what they themselves destroyed. The phenomenon among the colonized is more complex—a nostalgia for order or modernity that erases the violence and exploitation that accompanied them.

— Renato Rosaldo, "Imperialist Nostalgia," Representations, 1989

Internalized Shame

More insidious than nostalgia is the internalization of colonial value systems—the sense that indigenous traditions are inferior, embarrassing, or primitive.

Language: In both Morocco and India, colonial languages (French, English) retained prestige after independence. Fluency in the colonial language became a marker of education, class, and modernity.

"The colonized is elevated above his jungle status in proportion

to his adoption of the mother country's cultural standards."

— Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

Bodies and Performance: The shame attached to the Shikhate and devadasi traditions did not end with colonialism. Families continue to hide this heritage. The slurs derived from these traditions—Thevadiya in Tamil, Shikha as insult in Darija—carry colonial moral judgments into the present.

The Colonial Gaze in Visual Culture

Colonial photography and postcards created a visual vocabulary for representing the "Orient"—exotic, sensual, timeless, available for consumption. This visual vocabulary persists.

Orientalist Postcards: French colonial postcards depicted Moroccan and Algerian women in staged "harem" scenes—unveiled, eroticized, available to the European gaze. These images circulated widely and shaped European perceptions of North Africa.

Malek Alloula analyzed French colonial postcards, demonstrating how these images constructed Algerian women as objects of colonial fantasy while the women themselves had no control over their representation.

— Malek Alloula, The Colonial Harem, University of Minnesota Press, 1986

Contemporary Persistence: Similar visual tropes appear in contemporary travel photography, fashion shoots, and tourism marketing. The "exotic" other remains available for visual consumption.

Who Owns the Past?

Colonial archives—the documents, photographs, and objects that record colonial rule—are often held in the former metropole. The Archives Nationales d'Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence holds French colonial records for Morocco, Algeria, and other territories. The British Library holds the India Office Records.

This creates a fundamental asymmetry: the colonized must travel to the colonizer's country to access their own history.

Repatriation debates: Recent years have seen growing demands for the return of colonial archives and artifacts. In 2018, the Sarr-Savoy Report commissioned by French President Macron recommended extensive returns of African cultural heritage. Similar debates concern archival materials—digitization offers partial solutions, but questions of ownership and access remain.

Memory and Forgetting

How do societies remember—and forget—colonial violence?

Official Memory: Postcolonial states construct official narratives of resistance and liberation. Independence Day celebrations, national museums, and school curricula emphasize heroic struggle against colonialism.

Unofficial Memory: But colonial categories and values persist in everyday life—in language, in aesthetic preferences, in social hierarchies. This is what scholars call colonial mentalityகாலனித்துவ மனநிலைKālaṉittuva maṉanilaiThe internalization of colonial values and hierarchies by the colonized, persisting long after formal independence.: the internalization of colonial frameworks that continues long after formal independence.

Living with Colonial Memory

Morocco: Moroccans navigate between Arabic, Amazigh, and French—each carrying different historical weights. French remains the language of business, higher education, and elite culture. Arabization policies, themselves a reaction to colonialism, have sometimes marginalized Amazigh speakers. The Amazigh cultural movement, gaining strength since the 1990s, seeks recognition for identities that predate both Arab and French presence.

India: Indians navigate between English, Hindi, and regional languages with similar complexity. English-medium education remains a marker of privilege. Regional language movements assert identities against both colonial English and postcolonial Hindi centralization. Caste categories, solidified under colonialism, structure everything from marriage to politics.

In both countries, the colonial past is not past—it is the contested ground on which present identities are constructed.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press, 1967 [1952].

Alloula, Malek. The Colonial Harem. University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Rosaldo, Renato. "Imperialist Nostalgia." Representations 26 (1989): 107–122.

Dirks, Nicholas B. Castes of Mind. Princeton UP, 2001.

Sarr, Felwine, and Bénédicte Savoy. The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. 2018.

Digital Echoes

"When you type 'Devadasi' on YouTube, you'll get resources. Type the contemporary term—nothing. It's censored."

— Abirami

Colonial categories do not merely persist—they proliferate. In the digital age, slurs derived from colonial-era stigmatization spread across social media platforms, amplified by algorithms designed to maximize engagement. The shame manufactured in the nineteenth century finds new vectors in the twenty-first.

This chapter traces how terms like ThevadiyaதேவடியாThevadiyāDerogatory Tamil slur derived from "Devadasi" — one of the most common gendered insults, carrying colonial moral judgments into digital spaces. and ShikhaشيخةShīkhaOriginally an honorific ("woman of knowledge"), now used in Moroccan Darija to shame women by associating them with the stigmatized Shikhate. travel through digital spaces, transforming from historical categories into weapons of online harassment.

From Honorific to Slur

The linguistic journey is remarkably similar across both contexts:

TAMIL

தேவதாசி

Devadasi — "Servant of God"

↓

Colonial stigmatization

Anti-Nautch movement (1890s)

Abolition Act (1947)

↓

தேவடியா

Thevadiya — common slur

MOROCCAN ARABIC

شيخة

Shikha — "Woman of knowledge"

↓

Colonial + reformist stigmatization

Urban/rural divide

20th century marginalization

↓

شيخة

Shikha — insult in Darija

Tamil: The word "Devadasi" (தேவதாசி) once designated women of ritual importance. Through colonial stigmatization and the Anti-Nautch movement, it became associated with prostitution. Today, "Thevadiya" (தேவடியா) is one of the most common slurs in Tamil, used to demean women by implying sexual immorality. Most speakers who use it are unaware of its etymology—that they are perpetuating a colonial judgment every time they deploy the word.

Moroccan Arabic: "Shikha" (شيخة) was an honorific—the feminine form of "Sheikh," denoting a woman of knowledge or authority. Through colonial and reformist stigmatization, it became an insult in Moroccan Darija. To call a woman a "Shikha" today is to impugn her morality, to associate her with the stigmatized world of female performance.

The Digital Amplification of Shame

Social media platforms have become vectors for the rapid spread of gendered slurs. What once circulated within local communities now reaches global audiences instantly.

Platform Dynamics: Algorithmic amplification promotes content that provokes strong emotional reactions—including outrage and shame. Anonymity allows users to deploy slurs without accountability. Virality means a single shaming post can reach millions within hours. And digital permanence makes shame inescapable.

Research on online harassment in South Asia documents how caste and gender intersect in digital abuse. Women who violate expected gender roles are "put in their place" through slurs that invoke colonial-era stigmatization.

— Sambasivan et al., "Gender and Digital Abuse in South Asia," CHI Conference, 2019

The Untranslatability of Shame

One striking feature of these slurs is their untranslatability. "Thevadiya" cannot be adequately translated into English—its full force depends on the specific history of devadasi stigmatization, caste dynamics, and Tamil gender norms.

This untranslatability means: Platform moderation fails—content moderation systems trained primarily on English-language hate speech miss slurs in Tamil, Darija, and other languages. Context collapses—the historical weight of the slur is invisible to those outside the linguistic community. Harm continues—women are harassed in ways that platforms cannot or do not address.

Searching for Shame

Search engines and autocomplete functions reveal the persistence of colonial categories. Type "Devadasi" or "Shikha" into a search engine and observe what the algorithm suggests—what questions people are asking, what associations the system has learned.

The algorithm learns from collective behavior, and collective behavior carries colonial inheritances. The result is a feedback loop: stigmatizing content is searched for, which elevates stigmatizing content, which shapes what future searchers find.

Who Profits from Colonial Categories?

Digital platforms profit from engagement. Content that provokes shame, outrage, and conflict drives engagement. Colonial categories—with their deep emotional resonance and their capacity to wound—are profitable for platforms even as they harm users.

This creates a structural problem: platforms have financial incentives to allow the circulation of harmful content, while those harmed—often women, often from marginalized communities—bear the costs.

Dalit activists have documented systematic failures to address caste-based abuse online. Women's rights organizations in Morocco have highlighted the harassment faced by women in public digital spaces. The platforms profit; the communities suffer.

— Equality Labs, "Caste in the United States," 2018

Reclaiming Digital Space

Not all digital dynamics are harmful. Social media also enables:

Counter-narratives: Scholars, activists, and artists use digital platforms to share accurate histories of devadasi and shikhate traditions, challenging stigmatizing representations.

Community building: Diaspora communities connect across distances, sharing cultural knowledge and supporting one another.

Artistic reclamation: Musicians and dancers use platforms like YouTube and Instagram to perform and celebrate traditions that were stigmatized, reaching audiences their predecessors could never have accessed.

Hashtag activism: Campaigns like #DalitLivesMatter and feminist movements in Morocco create space for marginalized voices to speak back to power.

Toward Digital Dignity

What would it mean to build digital spaces that do not reproduce colonial harm?

Platform reform: Multilingual content moderation that understands context. Accountability for algorithmic amplification of harassment. Meaningful consultation with affected communities.

Digital literacy: Education about the colonial origins of common slurs. Critical media literacy around "vintage" and "exotic" aesthetics. Understanding how algorithms shape what we see.

Community-led archives: Digital archives controlled by descendant communities. Contextual framing determined by those most affected. Access policies that prioritize dignity over engagement.

Sambasivan, Nithya, et al. "'They Don't Leave Us Alone Anywhere We Go': Gender and Digital Abuse in South Asia." CHI Conference, 2019.

Equality Labs. Caste in the United States: A Survey of Caste Among South Asian Americans. 2018.

Punzalan, Ricardo L., and Michelle Caswell. "Critical Directions for Archival Research." The Library Quarterly 86, no. 4 (2016).

Gopal, Meena. "Digital Caste: Social Media and Caste Relations in India." Economic and Political Weekly, 2016–present.

The Body is a Festival

"El cuerpo es una fiesta."

— Eduardo Galeano

This exhibition has traced a history of shame—manufactured, imposed, inherited. But shame is not the end of the story.

Across Morocco and India, artists, scholars, and communities are reclaiming traditions that colonialism sought to destroy. The Shikhate still perform. Dancers still move. The body, despite everything, remains a site of joy.

This epilogue is not a conclusion but an opening—toward futures in which colonial categories no longer define what is sacred, what is art, what is worthy of dignity.

Reclamation

Morocco: The Aïta Lives

The Aïta tradition never died. Despite marginalization, despite stigma, the Shikhate continued to perform at festivals and celebrations across rural Morocco. Today, a new generation of scholars and artists is working to document, preserve, and celebrate this tradition.

Contemporary musicians draw on Aïta in fusion projects, bringing its rhythms and poetry to new audiences. Ethnomusicologists record and archive performances that might otherwise be lost. Cultural festivals increasingly include Aïta alongside the "classical" Andalusian music that colonial hierarchies elevated.

The stigma has not disappeared. But it is contested. Women who perform Aïta today do so in a context where their art is increasingly recognized as heritage—not shame.

India: Dancing Forward

The descendants of devadasi communities continue to navigate complex legacies. Some have reclaimed dance, performing traditions their grandmothers were forbidden to practice. Others have become scholars, documenting histories that were nearly erased.

Contemporary Bharatanatyam dancers increasingly acknowledge the devadasi origins of their art. Some seek out surviving practitioners from hereditary communities, learning repertoire that the "revival" had sanitized away. The dance scholar Nrithya Pillai, herself from a devadasi lineage, performs and teaches in ways that honor rather than erase her community's contributions.

The conversation has shifted. Where once the devadasi past was hidden, today it is increasingly a subject of scholarly attention, artistic exploration, and community pride.

The Work of Memory

This exhibition is itself an act of memory-work. By placing Moroccan and Indian histories side by side, we reveal patterns that might otherwise remain invisible. By naming colonial violence, we refuse to let it pass as natural or inevitable.

But memory-work is never complete. Archives remain fragmentary. Voices remain missing. The women at the center of these histories—the devadasis who danced, the shikhate who sang—left few records in their own words. We reconstruct their lives from the records of those who sought to reform, abolish, or classify them.

This exhibition honors their presence while acknowledging its limits. We cannot speak for them. We can only work to ensure their stories are not forgotten.

What We Owe

What do we owe to histories of harm?

Acknowledgment: The first step is naming what happened. Colonial categories were not natural. Shame was manufactured. Traditions were suppressed, transformed, and stigmatized through deliberate policy.

Restitution: Archives held in former colonial capitals should be accessible to the communities whose histories they contain. Cultural heritage should be returned. Digital archives should be controlled by descendant communities.

Transformation: The slurs that circulate in everyday language carry colonial violence. Every time we use "Thevadiya" or deploy "Shikha" as an insult, we perpetuate that violence. Language can change. Categories can be refused.

Celebration: The traditions that colonialism tried to destroy deserve celebration—not as museum pieces, but as living arts. The Shikhate deserve recognition as poets and artists. The devadasi legacy deserves honor, not shame.

"We are not what they said we were.

We are what we have always been:

artists, poets, keepers of tradition.

The shame was never ours."

About This Exhibition

Policing Native Bodies: A Dual Archive emerged from a collaboration between two researchers working across colonial histories. We came to this project from different archives, different languages, different colonial contexts. What we found was resonance: the same logics of classification, the same targeting of female performers, the same transformation of honor into shame.

By placing these histories together, we hope to reveal the structures that connect them—and to imagine futures beyond colonial categories.

Digital Global South Fellowship 2024–2025

Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH)

University of Luxembourg

The Researchers Behind This Archive

Ferdaous Affan

Morocco → University of Luxembourg

"This work of deconstruction, of trying to be aware of this internalized hatred towards your own identity and culture—it is such huge work one has to do on oneself."

PhD Researcher, C²DH

Computational analysis of colonial propaganda using LLMs

Abirami Raveendranath

Tamil Nadu, India

"There was a period in my life where I so desperately wanted English to be my mother tongue. That is so sad. Tamil is such a beautiful language."

Digital Global South Fellow 2024-25

Devadasi history & digital narratives